Volatile Organic Compounds

City Hall’s REAL response to West Dallas “Recycling” Fire? Let the EPA call the TCEQ in Fort Worth

Move along. Nothing to be alarmed about. We asked the manager.

Back on December 11th, there was a serious fire at the “Sunshine Recycling” facility in West Dallas, aka, another West Dallas scrap and junk yard. Beginning at around 3 in the afternoon and continuing to burn overnight, it produced huge clouds of dark thick smoke that covered whole blocks and could be seen for miles on its way toward Irving. There were still “hotspots” requiring attention the morning after, 20 or more hours after ignition.

A Dallas Fire Department spokesperson reported cars, appliances and “other scrap” were burning with intensity.

So if you lived in the neighborhood, you might have been relieved to see your local city council member post on his FaceBook page that “The Fire Dept has conducted testing and there is no hazardous materials burning.”

You might have been reassured to hear the authorities claim, and news media report, that a Dallas Fire Department Hazardous Materials Team was on site.

But none of that was true.

After a lengthy Open Records Act request by Downwinders, many phone calls and emails, we can now piece together what really happened. The Dallas Fire Department never showed up with its Hazardous Mat unit. It never did any air monitoring at the fire. It did no testing.

Instead, at some point that afternoon, as she looked out her window at FountainPlace downtown and saw the fire’s plume wafting only a few miles away, Superfund Division Chief Susan Webster at the Regional EPA office called the Texas Commission of Environmental Quality’s regional office in Fort Worth and asked the state to send someone over to monitor the fire’s smoke. Whether she did this knowing the Dallas Fire Department had already decided not to do any air monitoring itself, or whether is was double-checking is not known. Ms. Webster wouldn’t return our phone calls.

Was seeing this plume from her downtown office building what caused EPA’s Susan Webster to request TCEQ monitoring?

At around 4:30 pm Dallas Fire Department dispatch notes a call from “PCAQ” asking whether the City’s own Haz Mat team was on site and whether any air monitoring was going on. Ted Padgett, a Chief with the DFD, says that “PQAC” was really the “TCEQ” but was misunderstood on the phone.

Told no testing was going on, the TCEQ regional office in Fort Worth begins to assemble a site team and get their own monitoring equipment packed to go – hand held portable monitors.

This is the TCEQ side of that call: “TCEQ staff confirmed, via media coverage and contact with the Dallas Office of Emergency Management (OEM), that a fire was occurring at a scrap metal yard in Dallas. However, staff could not confirm the status of the fire nor what specifically was burning.” Emergency response in the Information Age.

The TCEQ monitoring team shows up in West Dallas at 6 pm – three hours after the fire has started.

Once there, the TCEQ monitoring team has the capabilities to monitor two pollutants: Particulate Matter (PM) and Volatile Organic Chemicals, or VOCs. They took one background sample away from the fire and four samples of about five minutes apiece downwind of the smoke.

The team says it doesn’t find significant VOCs in the air, but of course it’s possible those kinds of highly flammable materials like Benzene (via gas lines and tanks in the burning cars) had already been burned off. The category of VOCs is broad and covers a lot of sins, but it’s not the definitive list of “toxic chemicals” by a long shot. We know burning plastic will produce lots more Dioxins and Furans – the stuff that made Agent Orange so deadly. We know PM pollution can carry lots of bits of metals and other chemicals on them.

We know this because there was a very similar, if slightly more bureaucratic 21-year continuous incineration of car parts, plastics, used oil, dashboards, and scrap at the TXI cement plant in Midlothian, just south of the Tarrant/Dallas County lines. When you look at the before and after volumes of weird laboratory-induced chemical names you can’t really pronounce coming out of the stacks at tests controlled by the company, there’s no question burning junk fills the air full of junk too.

But it you don’t look for it, you won’t find it.

TCEQ was only looking for two kinds of pollutants that night, so it didn’t find anything else. It didn’t even bother to collect PM samples for “chemical characterization” – that is, determine what, if any, toxic baggage like lead or arsenic the PM particles were allowing to hitch a ride on them during the fire. Without such samples, it’s impossible to say the plume was not “toxic” in the “Really-Bad-For-You,” traditional regulatory meaning of that term.

Then there’s what the TCEQ team did find.

TCEQ recorded only four PM samples the whole evening. Half were alarmingly high: 113 ppb near the intersection of Singleton and Westmoreland, over three miles away, and 180 ppb near the intersection of Chalk Hill Road and Singleton between one and two miles from the fire.

Two other samples, one taken way north along Bernal And Hammerly, and further south down Westmoreland at Canyon Bluff showed “background” levels of PM at 14 ppb and 18 ppb respectively.

The EPA annual standard for PM exposure is 12 ppb, the daily standard is 35 ppb. The results from two of the four samples TCEQ took were three and five times the daily standard. That’s “toxic” in the “Science-Says-That-Stuff-Will-Kill-You” way.

The TCEQ inspectors left after only about an hour. No other monitoring took place for the duration of the fire, which was still going the next morning. So out of approximately 20 hours the incident lasted, only one was monitored.

TCEQ did note that the wind was out of the West at 10 mph and that “Potentially Impacted Receptors” included residences and businesses between Highway 12 and I-30.

There’s no record of the Dallas Fire Department, or anyone at Dallas City Hall, asking for the TCEQ’s monitoring results and TCEQ never sent them to anyone there. It wasn’t until Downwinders requested the results through an Open Records Request that any member of the public had seen the full record of what was done.

But some West Dallas residents complained about health effects from the fire to State Senator Royce West. One email the Senator got related how the fire had caused “my throat to become scratchy, coughing …. The smoke was so thick it hovered over all of West Dallas. The smell was horrific, very strong & lingering. You could smell it from loop 12 & all over West Dallas & I’m sure the lingering included other local surrounding areas in our city. The fire department said by it being cold outside, it causes the materials burning & the smoke in the air to continue to stay low where it affects us when breathing.“

Senator West’s office wrote a letter to the TCEQ regional office asking about what they’d found when they did their air monitoring. Here’s the reply he got:

“Smoke is a complex mixture of gases and fine particles. While the main pollutant of concern in smoke is the particulate matter, smoke may also contain other pollutants that are dependent on the product that is burnt, the moisture content of the product, and the fire temperature. Particles from smoke are often very small in size and have diameters that are 2.5 micrometers and smaller (PM 2.5). These particles are respiratory and eye irritants. Short-term exposures (hours-weeks) to these particles can cause headaches, respiratory (e.g., runny nose, scratchy throat, irritated sinuses, and bronchitis) and eye irritation (e.g., burning eyes). However, these symptoms typically disappear quickly once the person gets out of the smoke. Exposures to high concentrations of these particles can cause persistent cough, phlegm, wheezing, and difficulty breathing. While some people are more susceptible to the adverse health effects of smoke, particles from smoke can also cause respiratory symptoms, transient reductions in lung function and pulmonary inflammation in healthy adults. Children, older adults, and people with pre-existing heart or lung disease are more susceptible to lower levels of smoke than healthy people…(monitored) PM ranged from 0-180 ppb…..”

No mention of the scientific consensus that even short term exposure to low levels of PM can cause a host of permanent heath injuries, including brain and learning disorders, immune damage, and life-long respiratory ailments. No mention that fully half the samples taken by TCEQ were over 100 ppb and exceeded the 24-hour EPA standard for that specific pollutant. In fact, TCEQ says, all of your problems should disappear once you get out of the smoke – or your house, if the smoke from the toxic fire down the street is making it unlivable.

There’s an email from a TCEQ Special Assistant to the Deputy Director in Austin that asks: “…is there any way to put the highlighted PM detection in context….is this the level we would normally expect to find in smoke; at what level would we take action, can hand-held equipment quantify, etc?

She didn’t get a reply to those questions that we saw. Probably because no one at the Austin or Fort Worth TCEQ offices really knew the answers, or didn’t want to write them down and send them to a State Senator.

TCEQ was able to tell the Senator West that, despite plastics and metals and other materials on-site capable of producing toxic smoke, there were “no hazardous chemicals” on-site or involved in the fire.

How did it know? TCEQ inspectors asked the manager of the facility. There was no independent inspection.

And that, Dear Citizens, is how you’re protected by potentially toxic fires in Dallas, Texas. Feel safer?

Homes along Singleton probably exposed to some of the worst fallout of the December 11th fire.

Along with the high PM levels our PM Committee found in Joppa, this incident is another case study of why Dallas should have its own 24/7/365 dense network of air quality monitors – monitors that will be there when such a fire starts, as well as when it’s finally extinguished. Monitors who won’t make the value judgement about when the A Team should be called out. Because along with all the other questions this response poses you have to ask yourself if something like this happened in Preston Hollow or Uptown, would the Dallas Fire Department have still shown-up without its hazardous materials crew in tow?

This incident is Exhibit A why Dallas should also be incorporating public health into emergency responses. Why doesn’t the Fire Department have access to its own toxicologist or public health expert who could tell them what to sample for, where to sample, and whether the fire really posed any concern to neighbors or not? Why isn’t the automatic response to a fire like this to send out its own hazardous materials team instead of outsourcing it to TCEQ, 30 minutes away in Fort Worth?

December 11th allows us to peak behind the the modern post 9/11 facades of “Public Safety” and “Emergency Response” we all take for granted and see what a decrepit cynical reality is in charge of assuring us that “there’s no reason to be concerned.” That’s why we need a new reality.

Monthly TEDX Teleconference Tutorial on the Hazards of Fracking

Founded by the late great Theo Colburn, who along with her co-authors of "Our Stolen Future" way back in 1996 just about invented the field of "endocrine-disrupting chemicals," the Endocrine Disruption Exchange (TEDX) is holding a monthly teleconference series begining in April focusing on chemicals associated with fracking.

Founded by the late great Theo Colburn, who along with her co-authors of "Our Stolen Future" way back in 1996 just about invented the field of "endocrine-disrupting chemicals," the Endocrine Disruption Exchange (TEDX) is holding a monthly teleconference series begining in April focusing on chemicals associated with fracking.

First up on Thursday, April 7th at 1 pm is Dr. Chris Kassotis, who's been looking at the connection between fracking chemicals and surface and ground water contamination near fracking sites. According to the TEDX release, Kassotis will speak about…

"…his recently published research demonstrating increased endocrine disrupting activity in surface and ground water near fracking wastewater spill sites, as well as nuclear receptor antagonism for 23 commonly used fracking chemicals. His studies have shown prenatal exposure to a mixture of those chemicals at likely environmentally relevant concentrations resulted in adverse health effects in both male and female C57 mice, including decreased sperm counts, modulated hormone levels, increased body weights, and more. Dr. Kassotis will also discuss his recent work showing increased receptor antagonism downstream from a wastewater injection disposal site.

Dr. Kassotis is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University. He completed his PhD at the University of Missouri working with Susan Nagel to assess unconventional oil and gas operations as a novel source of endocrine disrupting chemicals in water, and the potential for adverse human and animal health outcomes from exposure.

This April get together is one of three briefings being given from now until June. According to a preview of the next two calls:

Thursday May 5, 2016, 1:00 pm Central – Dr. Shaina Stacy will discuss "Perinatal outcomes and unconventional natural gas development in Southwest Pennsylvania"

Thursday June 2, 2016, 1:00 pm Central – Dr. Nicole Deziel will discuss "A systematic evaluation of chemicals in hydraulic-fracturing fluids and wastewater for reproductive and developmental toxicity"

You have to go online and register as a participant if you want to listen in or ask quesitons via a live chat line.

How to Outflank HB40 in the Barnett Shale

Last week, the EPA made an important admission.

Last week, the EPA made an important admission.

"Methane emissions from the oil and gas industry are significantly higher than previous official estimates, according to draft revisions of the U.S. greenhouse gas emissions inventory released Monday by the Environmental Protection Agency. At 9.3 million metric tons, revised estimates of 2013 emissions are 27% percent higher than the previous tally. Over a 20-year timeframe, those emissions have the same climate impact as over 200 coal-fired power plants."

This most recent analysis jives with other studies like the one from UTA/EDF that found Barnett Shale facilities leaking up to 50% more methane than previously estimated. In reaction to the information, EPA Chief Administrator Gina McCarthy was quoted as saying "we need to do more" to cut methane pollution.

In its last year in office the Obama administration is finally grasping that natural gas isn't the climate change wunderkind its promoters claimed and last week's announcement is the tacit admission they need to do more to crack down on oil and gas.

What has that got to do with DFW in 2016?

By Spring, the Regional office of the EPA is expected to announce that it has rejected the State's clean air plan for DFW in regard to its application of "Reasonably Available Control Technology." That means the state hasn't required the application of readily-available air pollution controls for major sources the way the Clean Air Act demands. Specifically, EPA staff have cited the failure of the state to lower the emission standards for the Midlothian cement kilns to reflect more modern technology. But it's not the only area where Texas fell short. There are no new pollution requirements for any oil and gas facilities in the state's plan either.

EPA rejection of the Technology section of the state's DFW air plan would mean the EPA would begin to draft its own clean air plan for the region. An EPA-drafted plan gives local citizens concerned about the health impacts of fracking an opportunity to persuade the Agency to use the plan to crack down on smog-forming Nitrogen Oxide (NOx) and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) pollution in the Barnett Shale by requiring lower emission standards on all aspects of drilling and production.

While methane isn't considered a smog pollutant, it doesn't get emitted by itself. It comes out of a stack or valve, or leaks from a pipeline combined with smog-forming VOCs. So the more you control VOC pollution, the more you control methane pollution.

In light of last week's announcement, this gives EPA an extra incentive to go after VOC emissions in DFW even though the conventional wisdom is that it's combustion-generated Nitrogen Oxide pollution that really makes DFW smog so bad.

BTW, that conventional wisdom is under attack because the worst-performing air monitoring sites in North Texas are all in the Barnett Shale and heavily influenced by pollution from oil and gas facilities – both NOX and VOCs. It's possible to imagine a strategy to get smog numbers down in DFW solely by application of oil and gas emission regulations that can impact these important monitors – which drive the entire region's fate – even if the new regs have minimal impact on monitors elsewhere.

What kind of new regulations are we talking about?

* Start with the electrification of all 650 large natural gas compressors in the 10-county area.

* Do the same thing for all drilling rigs in the same 10-county area – nothing but electric.

* Emission standards for tanks and pipelines that reflect the latest leak-detection technology.

Inclusion of new EPA “Control Technique Guidelines" which are part of Agency's new methane rules. According to the Agency's release on the the new rules, “…reduction of VOC emissions will be very beneficial in areas where ozone levels approach or exceed the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for ozone."

Under the new rules, areas like DFW that host large concentrations of gas pollution sources and are officially categorized as “non-attainment” for smog receive "an analysis of the available, cost-effective technologies for controlling VOC emissions from covered oil and gas sources."

There's one more reason EPA has an incentive to go looking for all the cuts in oil and gas pollution it can find in the 10-county DFW non-attainment area: after the cement kilns, there's no other major sources the Agency can target locally.

Because while it has the authority in a federal clean air plan to regulate all pollution sources in that 10-county DFW non-Attainment area, the EPA can't write new emission standards for the East Texas coal plants located 100 miles outside of that 10-county area – even though those coal plants have more of an impact on North Texas smog than any other source of pollution. EPA (and us) can put pressure on the state to address these dinosaurs, but it can't touch them through a DFW air plan.

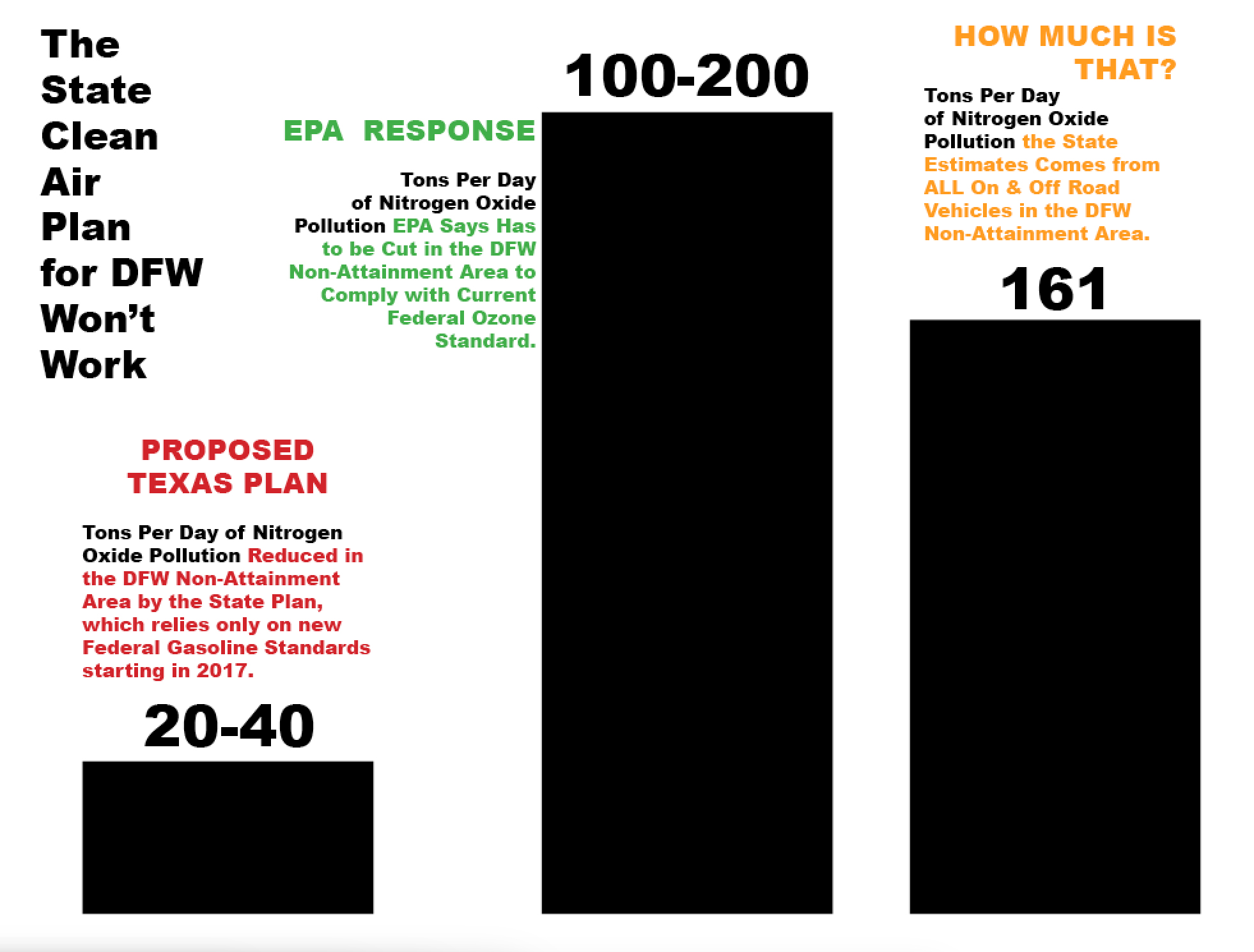

EPA staff has estimated it will take a cut of 100-200 TONS PER DAY in local smog-forming Nitrogen Oxide pollution for DFW reach the current 75 parts per billion smog standard. The State's "plan" – i.e. the federal gasoline fuel changes it relies on – only represents a 20-40 tons per day cut.

Where do the other 60 -160 tons a day in cuts come from?

To give you some idea of the size of that gap, the state estimates that all on and off road vehicles in the 10-county area will emit 161 tons per day of NOx in 2018.

State-of-the-art controls on all the cement plants might give you up to 15 tons a day. Electrification of the large compressors, another 15-16 tons per day eventually. After that it gets hard to find large volumes of cuts without the coal plants. And this is why the EPA should give cuts in VOC/methane a longer look than they have before – they're concentrated in the same areas where the region's worst-performing monitors are and they represent a huge source of climate change pollution that could also be another skin on the wall in addition to lowering smog levels.

There's no question the passage of HB40 has stymied grassroots progress toward more protective regulation of fracking by municipal governments in the Barnett Shale. It's thrown what was a fairly successful local movement into disarray. To date, there doesn't appear to be any consensus about strategies to combat the effects of the legislation.

But a way to outflank some of the impacts of HB 40 coming is coming down the pike, and it offers local fracktivists an opportunity to rally round a common, achievable goal – lowering emission levels across the board in the Barnett Shale. We can overlay a larger, stricter regional template for oil and gas regulation in place of 100 separate municipal ones.

What better way to nullify the efforts of the nullifiers in Austin?

It’s a Texas vs EPA Cage Match. Winner Takes All …The Air You Breathe

JOIN OUR TAG TEAM EFFORT TO TAKE DOWN THE STATE OF TEXAS

JOIN OUR TAG TEAM EFFORT TO TAKE DOWN THE STATE OF TEXAS

BUT WATCH OUT – THEY PLAY DIRTY

NEXT THURSDAY EVENING

JANUARY 21st

6:30 PM

616 Six Flags Road

First Floor HQ of the

North Central Texas Council of Governments

There's an important bureaucratic cage match between EPA and the State over how clean your air should be.

The state says just by hitching a ride on already-in-progress federal gasoline mix for cars and trucks, DFW ozone, or smog, will drop to levels "close enough" to the current federal smog standard of 75 parts per billion (approximately 78 ppb) . No new cuts in pollution required.

The EPA says not so fast – "close enough" may not be good enough this time around and you're not following the Clean Air Act in laying back and requiring no new cuts in pollution.

EPA has told Austin a failure to follow Clean Air Act rules will force it to take responsibility for the plan away from the State.

Is this something you want? If so, you should show up and next Thursday evening to give the EPA the political support it needs to pull the rug out from under the State.

WHAT HAS THE EPA ALREADY SAID ABOUT THE STATE'S PLAN?

Along with comments from DFW residents, environmental groups, doctors, industry and elected officials, EPA itself will weigh-in with written comments on the TCEQ plan by the deadline of January 29th.

But we don't have to wait that long to find out what EPA really thinks about what the State is proposing. Last year, EPA provided 11 pages of comments on exactly the same plan.

1) This plan won't work without more cuts in pollution

What EPA Said:

"Based on the monitoring data and lack of additional large reductions in NOx within areas of Texas that impact DFW, it is difficult to see how the area would reach attainment in 2018 based solely on federal measures reductions from mobile and non-road….The recent court decision that indicates the attainment year will likely be 2017 for moderate classification areas such as DFW, makes it less clear that the area will attain the standard by 2017 without additional reductions."

What EPA Meant:

It wasn't looking good when the deadline for reaching the 75 ppb standard was 2018 and the State didn't require any new cuts in air pollution, but now that the deadline is 2017, your do-nothing "close enough" plan is even less likely to work.

2) Your case for doing nothing isn't very good

What EPA Said:

"While the State has provided a large chapter on Weight of Evidence, the principal evidence is the recent monitor data. The monitor data does not show the large drops in local ozone levels and therefore raises a fundamental question whether the photochemical modeling is working as an accurate tool for assessing attainment in 2018 for DFW."

What EPA Meant:

Actual measurements of smog in DFW seem to undercut your claim that the air is getting cleaner faster. Maybe your computer model that's driving the entire plan isn't all that great. (And this was before smog levels went UP after the summer of 2015 – something not predicted by the State's model….)

3) Review pollution limits for the Midlothian cement kilns, or we'll reject your plan

What EPA Said:

"Because of significant changes in the type and number of cement kilns in Ellis County,…TCEQ's rules need to be reevaluated to insure these reductions are maintained, and the emission limits reflect a Reasonably Available Control Technology (RACT) level of control as required by the Clean Air Act…Failure to conduct a thorough RACT analysis for cement kilns which would include appropriate emission limits would prevent us from approving the RACT portion of the attainment plan submittal."

What EPA Meant:

Update your kiln pollution limits, or this part of the plan is toast. (Texas chose not to perform this update, in essence, giving EPA the bureaucratic finger.)

4) Oil and Gas pollution seems to be keeping the region's smog levels higher than they should be

What EPA Said:

"Recent NOx trends (Figure 5-10 in TCEQ's Proposal) indicate a fairly flat NOx trend for several NO monitors in the western area of the DFW area (Eagle Mtn. Lake, Denton, and Parker County monitors). These monitors are in areas more impacted by the growth in NOx sources for Oil and Gas Development that seem to be countering the normal reduction in NOx levels seen at other monitors due to fleet turnover reductions (on-road and Nonroad). These higher NOx levels in the modeling domain that seem to be fairly flat with no change since 2009

raise concern that the area is not seeing the NOx reductions needed to bring the ozone levels down at these monitors."

What EPA Meant:

Since the historically worst-performing air pollution monitors in DFW are located in exactly the same area as a lot of gas and oil activity, and these monitors haven't been seeing the expected decrease in smog you predict, maybe you ought to think about cutting pollution from those oil and gas sources. Like we said, this plan needs more cuts in pollution.

5) Your own evidence supports cuts in pollution from the East Texas Coal Plants

What EPA Said:

"The TCEQ provided an evaluation of emissions from all of the utility electric generators in east and central Texas. However, the discussion in Appendix D on the formation, background levels, and transport of ozone strongly supports the implementation of controls on NOx sources located to the east and southeast of the DFW nonattainment area. How would a reduction in NOx emissions from utility electric generators in just the counties closest to the eastern and southern boundaries of the DFW area impact the DFW area?"

What EPA Meant:

Despite your protests, the State's own analysis shows cuts in pollution from the East Texas Coal Plants have a big impact on DFW smog levels and supports the argument for putting new controls on them. Did you actually run your fancy-dancy computer model to see what would happen if you did that? (No, the State did not. But UNT and Downwinders did.)

WHY WOULD AN EPA PLAN FOR DFW AIR MAKE ANY DIFFERENCE?

If the EPA rejects the State's plan, the clock begins ticking: the State is warned it has to write a new plan and, meanwhile, EPA begins to write its own. If the State doesn't turn in a plan the EPA finds acceptable in 24 months, the EPA plan is implemented instead.

The State has no interest in any new cuts of pollution from any sources. It thinks it's plan is already "close enough."

If the EPA is writing the plan, citizens can use the new UNT study to show the Agency which cuts get the largest drops in smog – using the State's own air model.

We can use Dr.Haley's study to show the approximate economic and public health benefits of those cuts.

More change happens if EPA is writing the plan.Enough to finally get DFW safe and legal air? We don't know until we try. The alternative is doing nothing.

The Impact of the EPA’s New Methane Rules on the Barnett Shale? TBD

Despite all the gnashing of teeth by industry and hallelujah choruses from the Big Green groups, the new methane rules proposed by the Obama Administration this last week have no immediate impact on facts on the ground in the Barnett Shale.

Despite all the gnashing of teeth by industry and hallelujah choruses from the Big Green groups, the new methane rules proposed by the Obama Administration this last week have no immediate impact on facts on the ground in the Barnett Shale.

That’s because, like the recent coal CO2 rules, they regulate future facilities, not the 17,000 or so wells, plus infrastructure, already operating in the Barnett.

They do bring a welcome spotlight to “downstream” facilities like gathering lines and compressors, which is where most of the methane in the gas fuel cycle escapes. They also concede the connection between methane releases and smog (“…reduction of VOC emissions will be very beneficial in areas where ozone levels approach or exceed the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for ozone”), as well as methane and more toxic Volatile Organic Compounds such as Benzene and Toluene (“The measures proposed in this action achieve methane and VOC reductions through direct regulation. The hazardous air pollutant (HAP) reductions from these proposed standards will be meaningful in local communities.”)

EPA’s new rules set a floor for emissions that the industry, over time, will eventually get closer to meeting as a while with the turnover of equipment. But that could take decades. Meanwhile, the agency is only offering “guidelines” to states with smog problems – like Texas – for new pollution controls to reduce methane at existing facilities.

Under this part of the regulation, areas like DFW that host large concentrations of gas pollution sources and are officially categorized as “non-attainment” for smog, or ozone, standards will supposedly be the beneficiaries of new EPA-written “Control Technique Guidelines.”

According to EPA, these CTGs “provide an analysis of the available, cost-effective technologies for controlling VOC emissions from covered oil and gas sources. States would have to address these sources as part of state plans for meeting EPA’s ozone health standards.”

If you live in Texas, you’ve already chortled at that last sentence. Really? The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) would have to use these new technologies on gas sources in their new clean air plans for DFW? Something they’ve refused to do for the last two clean air plan cycles dating back to 2010?

Well, they have to address them at least. And a lawsuit aimed at gutting the new rules is a form of addressing isn’t it?

These are guidelines only, up to the state to enforce – as the EPA admits. “States have some discretion in applying these guidelines to individual sources.” The leverage EPA has is that it still needs to approve these state-generated clean air plans and it can make an official determination that a state didn’t follow the guidelines and send it back to be amended.

This might not be all that important except that the State of Texas is going to have to write a new air plan for DFW in the next year or face the prospect of a federal plan being written in its stead. The one Austin submitted in July is already falling apart on several fronts, and TCEQ has to submit a whole new version or face an EPA-imposed one.

Will the state at least have to acknowledge these guidelines in this current air plan controversy? No. The states have two years to fold the proposed CTGs into their SIPs. So they don’t even have to come into play until this current state plan fails, and Austin or the EPA begin to write a replacement. And why might this plan fail? In part, because it doesn’t apply modern controls to major sources like oil and gas facilities.

You might remember in July, a total of 11 studies were collectively released that concluded the Barnett Shale was leaking 50 percent more methane than previously thought. The day before the EPA made its announcement this week, a national version of those studies estimated US methane pollution from oil and gas was being underestimated by 30%. That’s important because many models of air pollution used by the EPA and the states use those standard emissions estimates that now look obsolete. If you increase the amount of methane, and associated pollutants, by 30-50% in those models, the results might look very different.

So even though the state isn’t officially required to include this new approach to decreasing VOC pollution until 2017 or later, it’d be nice to see it adopted now and have an immediate impact on a region that has a longstanding chronic smog problem. But as long as Texas is in charge of writing DFW’s air plans, that’s just not gong to happen.

Worried Much? Gas Industry Desperate to Hold Back Truth and Mansfield Ordinance Reform

For almost a year, Mansfield residents have been trying to rewrite their city's drilling ordinance to better reflect the science surrounding the public health consequences of heavy industry taking place so close to people. During this entire time, and countless appearances before their city council, there has not been one Mansfield citizen who came forward and defended the current approach.

For almost a year, Mansfield residents have been trying to rewrite their city's drilling ordinance to better reflect the science surrounding the public health consequences of heavy industry taking place so close to people. During this entire time, and countless appearances before their city council, there has not been one Mansfield citizen who came forward and defended the current approach.

But now that the Mansfield council is ready to act on a new ordinance, the gas industry is doing exactly what it's always accusing their opponents of doing, sending outsiders in to invade the town and spread misleading information. And they're doing it in a big, desperate way. Let's just review what's happened in the last couple of weeks:

Industry hired a sleazy push polling firm to conduct a Mansfield campaign by phone that purposely misleads about the impact of the revisions to the ordinance being sought and makes personal attacks on the residents pursuing those revisions.

Sent in trade association speakers from Austin and Fort Worth to Mansfield to further mislead the business community about the revisions being sought.

Set up an e-mail site where industry employees, no matter where they live, send their comments to the Mansfield City Council, in opposition to any revisions.

And last night, (Sunday) the industry released a "study" purporting to show how safe the existing 600 foot setback was in Mansfield.

And these are just the things we know about right now. Having seen the huge multi-well Edge Resources permit get temporarily, but unexpectedly, tabled in January, the industry wasn't about to take any chances on seeing that happening again in their own back yard. So they've thrown everything and the kitchen sink into the Mansfield fight.

Of course, this reaction is a tremendous complement to the efforts of the intrepid Mansfield Gas Well Awareness group, that has, oh who knows, maybe a millionth of the budget the industry has already spent on these efforts. That the gas industry should be so frightened by calls for "responsible drilling" and more protective measures that have numerous precedents in the region tells you all you need to know about their insecurity post-Denton. It's almost comical.

Let's just take the latest effort that the Energy in Depth guys are generously calling a "study." Forget that if an environmental group were offering up such a thing, they'd be the first to point out its obvious bias. But of course, that objection disappears entirely when they fund the results. All of a sudden its a paragon of virtuous objective science. And mind you, these results were funded by the very gas operator who's well emissions are being sampled. No conflict of interest there.

Forget also that they're so proud of this work that they released it on a Sunday, after hours, the day before the Mansfield City Council takes up consideration of a new gas drilling ordinance. It's almost like they wanted to minimize the scrutiny of the thing.

Also put aside that this thing is not peer-reviewed or journal published – because the "science" is so poorly done that it could never pass review and get published in anything but an Energy In Depth blog post.

Also discount the love industry has for for testing levels of contaminants in the air versus its utter contempt for testing people and health. If you're going to claim as your working hypothesis that certain levels of contamination are completely harmless, and that anything that falls below certain levels is benign, then why not put that hypothesis to the test by performing an epidemiological study? But no, you see no such studies coming from industry, because they don't want to test that hypothesis.

One type of study is top, down. It looks at the levels of poisons in the air, and assumes that if they don't exceed the levels deemed dangerous by the regulatory arm of the industry , the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, then everything must be hunky dory.

The other is bottom-up. It looks at the health of people who live adjacent to the facility releasing the poisons and determines whether their health is worse than those who don't live in close proximity to polluters, whether they are receiving officially sanctioned levels of poisons are not.

The reason the second type of study is a truer snapshot of reality is because we keep finding out that levels of poisons we thought were safe turn out not to be safe at all. Go back even 20 years to the Exide lead smelter in Frisco, or 30 years to the RSR lead smelter in Dallas. Regulators and industry were routinely saying that levels of lead being released by these facilities were "safe." As it turns out, they were not. In fact, science now says there's no level of exposure to lead that cannot do harm to a person, particularly a child.

This learning curve can be applied to many, many types of chemical exposures over the last few decades, including Benzene, and other poisons routinely released by the gas industry. And it's why industry never wants to test its hypothesis about "safe" levels of things in the air with studies of what the actual health of people who live near their facilities is really like.

In reality, the best epidemiological studies to date, those that ARE done by third parties and ARE peer-reviewed an journal published, all conclude that living near gas mining operations increases the likelihood that you'll get sick. That's the state of the science. It's the same kind of science that proved cigarette smoking causes cancer. And that's why industry wants to stick to telling you about how safe the levels of poisons are in the air.

But forget all of that. Let's just take this "study" thing at face value. There was a 100 minutes of sampling of the air in 2012 at a gas pad site before drilling started, and in 2014, there were three 30 minute samplings of air around 600 feet away from the pad site after drilling had begun, and one sampling site well away from the pad to function as a background reading. That's it. That's the entirety of the study: the comparison of this "before" and "after" short term sampling.

Now if you were a high school chemistry nerd looking for a shot in the local science fair, you might insist that the procedures and testing protocol be the same for the before and after sampling. And you'd be right. But this study didn't bother.

In 2012, the sampling looked at Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), Sulfur Compounds and Formaldehyde "and other Carbonyl Compounds." In 2014, the sampling only looked at VOCs. so, only one-third of the original 2012 testing was duplicated. You'd think they were trying to intentionally ignore some poisons or something.

But it gets better. There were 15 separate VOCs sampled for in 2012, but only six, (less than half and only barely more than a third), of those were sampled for in 2014. In other words, the 2014 sampling not only left out two-thirds of the 2012 contaminant categories, it left out most of the chemicals in the one category it did sample.

In 2012, you had a total of 100 minutes of sampling of air in the middle of the pad site. In 2014, you had three 30-minute samplings of air 600 feet away from the pad site. They couldn't even replicate the sampling time.

As Texas Sharon has already pointed out, you might want to do your sampling with the same general kinds of weather – circumstances that might promise a representative sample. But no, not for this "study." There was only a trace of rain recorded at the site in 2012, but between half an inch of rain and two and a half inches of rain in the 2014 sampling. Of course, rain being in the air and all, that could affect your air sampling results.

The average wind speed was 6 to 11 mph in 2012, while in 2014, it was, well, the second report really doesn't say what the average wind speed was. It just says that the wind speed varied from 0 to 21 along with wind direction. But who needs details for real science right?

In 2014, none of the background samples were the highest levels of exposure found, that is, the highest readings of all chemicals found were downwind of the pad site.

Of the six VOCs sampled for in both 2012, and 2014, three were significantly higher in 2014.

Benzene was almost 4 times higher in 2014: .13 vs .49.

Toluene was almost three times higher in 2014: .35 vs .91.

Methyl Ethyl Ketones increased by a third: from .53 to .72.

And mind you this was in the rain with gusts up to 21 mph. Only m,p Xylene and Carbon Disulfide were lower in 2014.

In all, these chemicals were detected despite the crappy methodology used:

- Benzene

- Benzene, 1,2,4‐trimethyl‐

- Benzene, 1,3,5‐trimethyl‐

- Benzene, 1,3‐dichloro‐

- Benzene, 1,4‐dichloro‐

- Carbon disulfide

- Carbon Tetrachloride

- Cyclohexane

- Ethane, 1,1,2,2‐tetrachloro‐

- Ethane, 1,1,2‐trichloro‐1,2,2‐trifluoro‐ (Freon 113)

- Ethylbenzene

- Furan, tetrahydro‐

- Heptane

- Methyl Butyl Ketone (MBK)

- Methyl Ethyl Ketone (MEK)

- Methyl Isobutyl Ketone (MIBK)

- Methyl Methacrylate

- Methylene Chloride

- Naphthalene

- o‐Xylene

- m,p‐Xylene

- Styrene

- Tetrachloroethylene

- Toluene

- Trichloroethylene

- Trichloromonofluoromethane (Freon 11)

That's reassuring right? That's what the industry folks are saying, because guess what, they're all at levels below what TCEQ says are OK for you to breathe – for a total of 30 minutes per sample. Unfortunately, most of us have a hard time breaking our habit of breathing all the time. Everyday. For years on end.

Look, you don't need to be a scientist to know how full of holes this slap dash attempt at CYA actually is. Industry is just throwing one thing after another up on the wall and hoping it sticks for the time it takes for the Mansfield City Council to justify its rejection of the citizens' revisions. Especially the 1500 setback originally requested.

Industry keeps saying that this distance amounts to a "defacto" ban of drilling, but that's clearly not the case in Mansfield. It's own literature touts the fact that a rig can be more than a mile away from the gas deposit its mining. You can put a rig in an industrial zoning tract and still reach a pocket of gas underneath a neighborhood without the surface components being anywhere near each other.

So what's the real reason industry oppose these setbacks for heavy industry that would be more than appropriate for any other kind of heavy industry? It's because the gas industry doesn't want to be grouped with lead smelters, and cement plants, and refineries and other kinds of heavy industry. It operates under an industrial exceptionalism that's unique in the modern era. It wants to be viewed as the kindly, well-landscaped heavy industrial polluter. Because when you start seeing it differently, all the carefully-constructed mythology surrounding its operations becomes transparent – just like it did with lead smelters, cement plants and refineries.

Because of its massive infusions of cash and resources overwhelming Mansfield in the last couple of weeks, the industry may indeed forestall the inevitable a little longer in what it considers a jurisdiction that's bought and paid for several times over. But science marches on – the real sort – and it's not going to be very kind to this industry in the longer run. Even the Marlboro Man had to hang up his spurs. It's just a matter of time before this industry is viewed as just another nasty polluting cause of illness, even by those who've benefited from it the most.

Both Gas Industry Spinmeister and Mansfield Compressor Spew During Thursday’s EPA Hearing

There was at least one truth uttered by Steve Everley, the professional PR spokesperson for Energy in Depth, itself the PR arm of the Gas Industry, during his testimony at last Thursday's EPA ozone standard hearing in Arlington:

There was at least one truth uttered by Steve Everley, the professional PR spokesperson for Energy in Depth, itself the PR arm of the Gas Industry, during his testimony at last Thursday's EPA ozone standard hearing in Arlington:

"…natural gas producers will be significantly impacted by EPA’s proposal to reduce the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for ozone from 75 parts per billion to between 65 and 70 ppb."

Indeed. At the rate things are going in Austin and DC, it might be the only thing to impact the industry's large emissions of pollution for many years to come. Left unsaid by Everley was why the industry would be impacted by such a lower ozone standard – because in many parts of the country now, including the DFW area, smog-forming pollution from the gas industry is contributing significantly to higher ozone levels.

Even the governmental affairs branch of the gas industry, otherwise known as the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, admits that facilities like compressors, storage tanks, pipelines, and de-hydrators found by the thousands in the western part of the Metromess contribute more smog-forming Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) than all the "on-road" vehicles in North Texas combined. This is true not only at the present time, but will be true at least three years into the future, according to TCEQ's own estimates.

Gas facilities also account for the third largest source of smog-forming Nitrogen Oxide pollution in DFW, according to TCEQ numbers included in their recent air plan submitted to EPA – only a ton per day less than all "non-road" vehicles in North Texas like construction equipment, and well ahead of "point sources" like the Midlothian cement kilns and local power plants.

In all, TCEQ predicts that 35,335 tons per year of smog-forming pollution will still be coming from the region's gas industry in 2018. That's a lot. It's so much that, as the TCEQ also demonstrates with its computer modeling, even a tweak here and there in gas pollution estimates can make big differences in the levels of ozone at monitors in places like Denton and Keller and Eagle Mountain Lake – traditionally the worst-performing air quality monitors in North Texas.

And that's why a lower ozone standard is a threat to the industry. The very air quality monitors the industry affects most with its pollution are the ones driving the region's high smog levels. Lowering the ozone standard means it would have to spend money to reduce those emissions significantly. It means it would have to spend money to prevent the kind of huge "accidental" releases of smog-forming pollution released by the Mansfield compressor on Thursday even while Steve Everley was testifying to EPA.

After giving her own testimony to EPA on Thursday morning, Earthworks' Sharon Wilson and Mansfield Gas Well Awareness board member Lance Irwin headed out to the Summit Midstream Partners Compressor Station behind Mansfield's Performing Arts Center, with an infrared, or FLIR "thermal imaging" camera. Such a device is capable of recording the kinds of VOC emissions that are often smelled and inhaled by surrounding residents, but can't be seen with the naked eye.

The Summit compressor and the two nearby Eagleridge gas wells have been the scene of many different complaints from the surrounding Mansfield neighborhood – everything from airborne foam landing in backyards to oily deposits landing on car finishes. On Thursday, Wilson and Irwin were responding to a new series of complaints about awful smells. When they showed up, what the two recorded was a massive "emergency blowdown" (versus the "planned" kind). While filming the event, Wilson suffered health effects familiar to gas facility neighbors and was overwhelmed by the obvious hydrocarbon fumes. Once you see her video, you understand why:

Such a blowdown was exactly what Lance Irwin had warned the Mansfield City Council about only three days before, during comments directed at slowing down or denying the permit for a new compressor, 34 wells, 12 tanks and a assortment of other facilities at an Edge pad site near Debbie Lane in town. He pointed out that industry and government estimates about emissions never take these kind of catastrophic events into account – form a short-term toxic exposure perspective, or as it turns out, from an air quality, smog-creating perspective. And he's right.

In this regard, these kinds of accidents are no different than the infamous industrial "burps" from refineries and chemical plants along the Houston Ship Channel that lead to smog spikes downwind. There are 650 large compressor stations in the DFW "non-attainment" area. How many are experiencing blowdowns on any given day? How many are affecting ozone levels in the spring and summer? The TCEQ estimates included in its DFW air plan don't even try to quanify them.

Because gas facilities like compressors are subject only to "standard permits," are located diffusely around a region, and don't officially emit a de minimus amount of air pollution, they're not subject to the federal rule of off-setting. That's when a new polluting facility locates in an already smoggy area like DFW and has to pay to cut smog pollution elsewhere if it wants to emit the stuff itself. If a new cement plant or power plant were to locate in DFW, it would have to pay to reduce a ton and a half of smog-forming pollution for every ton it wanted to release. Gas facilities don't have to do this – even though collectively they emit more smog-forming pollution than all the cement plants and power plant in the non-attainment area!

EPA has tried to argue that a company's different facilities are all tied together and should be counted as a single source, and so subject to off-setting regulations. But the courts have ruled against them.

Rising gas industry pollution and the absence of any official brake on its growth like off-setting is a large reason, maybe the primary reason, why DFW hasn't seen the kind of air quality progress it should have by now. Until this last summer's cooler and wetter weather gave us relief, ozone levels had been stagnating or even rising since 2009 – or about the time the industry invaded North Texas in large numbers. There's no question that had the Barnett Shale boom not happened, we'd have much cleaner air by now.

But it did and we don't. And so that's why a lower ozone standard is perhaps the only way that the gas industry will ever be forced to clean-up its act – especially on the widespread regional level we require to get to safe and legal air. Just like it has with the Midlothian cement plants, the need for lower smog levels can force the state's and industry's to act to add controls. It's a long-term fight, but one of the only paths to across-the-board change versus the city-by-city slog activists have had to rely on.

National Resources Defense Council lawyer John Walke has a great takedown of Steve Everley's spin on Thursday. And the tireless cross-country DeSmogblog reporter and photographer Julie Dermansky has a good read on the Mansfield fight that you should check out. But the most compelling rebuttal to both industry PR and local governments who want to ignore their own responsibility in this mess is probably Wilson and Irwin's two and a half minutes of video.

TCEQ’s Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Air Plan for DFW

TCEQ Public Hearing on the new DFW Anti-Smog Plan

Thursday, January 15th 6:30 pm

Arlington City Hall, 101 W. Abram

Over the last two decades, we've seen some pretty lame DFW clean air plans produced by the state, but the newest one, scheduled for a public hearing a week from now, may be the most pathetic of the bunch.

From a philosophical perspective, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality stopped pretending to care about smog in DFW once Rick Perry decided to run for president around 2010 or so. Computer modeling was scaled back, staff was slashed, and the employees that were left had to be ideologically aligned with Perry's demand that no new controls on industry (i.e potential or existing campaign contributors) was preferable to six or seven million people continuing to breathe unsafe and illegal air.

TCEQ's 2011 anti-smog plan reflected that administrative nonchalance by concluding – in the the middle of the Great Recession – that consumers buying new cars would single-handedly deliver the lowest smog levels in decades. It did not. It went down in history as the first clean air plan for the area to ever result in higher ozone levels. The first, but maybe not the last.

This time around, it's not the cars themselves playing the role of atmospheric savior for TCEQ, but the fuel they'll run on. Beginning in 2017, the federal government is scheduled to introduce a new, low-sulfur gasoline that is predicted to bring down smog by quite a bit in most urban areas. Quite a bit, but not enough to reach the ozone standard of 75 ppb that's necessary to comply with the Clean Air Act by 2018. It's the gap between this official prediction and the standard where the state is doing a lot of hemming and hawing.

TCEQ staffers really did tell a summertime audience in Arlington that that estimated 2018 gap of between 1 and 2 ppb was "close enough" to count as a success. Now, you might give them the benefit of the doubt, but remember this is an agency that has never, ever been correct is its estimation of future ozone levels. After five attempts over the last two decades, TCEQ has never reached an ozone standard in DFW by the official deadline. Precedent says this plan won't even get "close enough."

Plus, we know getting "close" to 75 ppb isn't protecting public health in DFW. Even as this clean air plan is being proposed by Austin, the EPA is moving to lower the national ozone standard to somewhere between 60 and 70 ppb (There's a hearing on that at Arlington City Hall on January 29th). That new EPA ozone standard is due to be adopted by the end of this year. So this entire state plan is obsolete from a medical perspective. Instead of aiming for a level of ozone pollution closer to 70 ppb as soon as possible, it's not even getting down to a flat 75 ppb at all DFW monitors by 2018. It wil take an entirely new plan, and pulling TCEQ teeth, to do that much later. In other words, millions of people will have to wait as much as a five to seven years longer to get levels of air quality we know we need now in 2015.

What are the major flaws this time?

1. TCEQ is Using 2006 in 2014 to Predict 2018.

The EPA recommends that states use an "episode" of bad air days from the last three years – 2009-2013 – in trying to estimate what ozone levels will be three years from now. The more recent the data, the better the prediction.

TCEQ is ignoring that recommendation, relying on a computer model that's already nine years old. This has all kinds of ramifications on the final prediction of compliance. Instead of having more recent weather data, you have to "update" that variable. TCEQ doesn't have to compensate for the drought DFW is experiencing now or factor in a year like 2011 where the drought caused a worst case scenario for ozone formation.

TCEQ isn't using more recent data on how sensitive monitors are to Nitrogen Oxide (NOx) and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) – the major kinds of pollution that cause smog . That's important because gas production in the Barnett Shale has put a lot more VOCs in the air. But instead of getting a more accurate post-drilling boom read on what's driving smog creation, the TCEQ is relying on a picture that starts out before the boom ever started.

The further you reach back in time for a model to predict future levels of smog, the fuzzier that future gets, and the less accurate the results. TCEQ is using a model that's twice to three times older than EPA guidance recommends. What are the odds that TCEQ estimates will be correct based on this kind of methodology?

2. TCEQ is Downplaying OIl and Gas Pollution

Citizens attending the air quality meetings in Arlington over the past year have seen the TCEQ try and hide the true volume and impact of oil and gas pollution at every turn. Instead of all the industry emissions being listed under the single banner of "Oil and Gas Pollution," the Commission has tried to disperse and cloak them under a variety of categories in every public presentation.

"Other Point Sources," a classification that had never been seen before, was the place where pollution from the 647 large compressor stations in DFW could be found – if you bothered to ask. "Area Sources" was where the emissions from the thousands of other, smaller compressors could be found – again, only if you asked. "Drilling" was separate from "Production." And despite other agencies being able to tease out what kind of pollution came from the truck traffic associated with fracking within their jurisdictions, the TCEQ never bothered to estimate how much of the emissions under "Mobile Sources" was generated by the Oil and Gas industry.

The reason the TCEQ has tried so hard to hide the true volumes of oil and gas pollution is because once you add up all of these disparate sources, the industry becomes the second largest single category of smog-forming pollution in DFW, second only to on-road cars and trucks (and remember many of those trucks are fracking-related). According to TCEQ's own estimates, oil and gas facilities in North Texas produce more smog-forming VOC pollution than all of the cars and trucks in the area combined, and more smog-forming NOx pollution than the Midlothian cement plants and all the area's power plants combined.

TCEQ is loathe to admit the true size of these emissions and place them side-by-side next to other, traditional sources, lest the public understand just how huge a impact the oil and gas industry has on air quality. Austin's party line is that this pollution isn't contributing to DFW smog – that it's had no impact on local air quality. But such a claim isn't plausible. If cars are a source of smog, and cement kilns and power plants are a source of smog, how can a category of VOC and NOx pollution dwarfing those sources not also be a source of smog? Think how much less air pollution we'd have if the Barnett Shale boom of the last eight years had not taken place?

In it's last public presentation in August, the TCEQ made the impact of oil and gas pollution clear despite itself. According to the staff, oil and gas emissions were going to be decreasing in the future more than they had previously estimated. As a result, a new chart showed that certain ozone monitors, including the one in Denton, would see their levels of smog come down significantly. It was exactly the proof of a causal link between gas and smog that TCEQ had been arguing wasn't there. Only it was.

In terms of forecasting future smog pollution, TCEQ is underplaying the growth of emissions in the gas patch. Everything it's basing its 2018 predictions on is years out-of-date, leftover from its last plan.

Drilling rig pollution is extrapolated from a 2011 report that counts feet drilled instead of the actual number of rigs. TCEQ predicts a decline in drilling and production in the Barnett Shale without actually estimating what that means in terms of the number of wells or their location. It also assumes a huge drop-off in gas pollution after 2009 that hasn't been documented by any updated information. It's only on paper.

While recent declines in the price of oil and gas have certainly put a damper on a lot of drilling activity, there's still a significant amount going on. Look no further than Mansfield, where Edge is now applying for permit to build a new compressor and dozens of new wells on an old pad.

In 2011, nobody was building Liquified Natural Gas terminals up and down the Gulf Coast for an export market the way they are now. Analysts say those overseas markets could produce a "second boom" in drilling activity between now and 2018, but the TCEQ forecasts don't take that into account.

Gas production pollution numbers – emissions from compressors, dehydrators, storage tanks – are even more tenuous. Every gas industry textbook explains that as gas plays get older, the number of lift compressors increases in order to squeeze out more product. Increase the number of compressors and you increase the amount of compressor pollution. But TCEQ numbers fly in the face of that textbook wisdom and predict a decline in compressor pollution because wells in the Barnett Shale are getting older!

The best analogy for how TCEQ is estimating oil and gas pollution is its poor understanding of where those thousands of smaller compressor are and how much pollution they're actually producing. No staff member at TCEQ can tell you how many of those compressors there are in the region – they literally have no idea and no idea of how to count them in the real world. There are just too many, their locations are unknown, and they were never individually permitted.

Instead, the TCEQ takes production figures from the Railroad Commission and guesses how many of those small compressors there are, as well as their location, based on where the RRC tells it production is going on in the Shale. Then staff guesses again about the emissions being emitted by those compressors, because there's no data telling them what those emissions actually are. In the end you have a series of lowballed guestimates, stacked one atop the other, presented as fact. It's smoke and mirrors.

3. TCEQ Isn't Requiring Any New Controls on Any Major Sources of Air Pollution

Like its previous 2011 DFW air plan, which resulted in an increase in North Texas ozone levels, TCEQ's new plan requires no new controls on any major sources of air pollution, despite evidence showing that such controls in smog-forming emissions from the Midlothian cement plants, East Texas coal plants, and Barnett Shale gas facilities could cut ozone levels significantly.

Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) is already used extensively in the cement plant industry in Europe to reduce smog pollution by up to 90%. Over a half dozen different plants have used the technology since 2000. The TCEQ's own 2006 report on SCR concluded it was "commercially available." Holcim Cement has already announced it will install SCR in its Midlothian cement plant. Yet the TCEQ makes no mention of this in its plan.

That's right, a cement plant in Midlothian has decided SCR is commercially viable, but the State is looking the other way and pretending this development in its own backyard isn't even happening. TCEQ is stating in its proposed plan that SCR just isn't feasible!

In 2013, a UTA Department of Engineering study looked at what happened if you reduced Midlothian cement plant pollution by 90% between 6 am and 12 Noon on weekdays. Ozone levels went down in Denton by 2 parts per billion. That may not seem like a lot, but in smog terms it's the difference between the Denton air monitor violating the 75 ppb standard under the TCEQ plan and complying with the Clean Air Act.

In 2012 a UTA College of Nursing study found higher rates of childhood asthma in Tarrant County "in a linear configuration" with the plumes of pollution coming from the Midlothian cement plants. SCR means less pollution of all kinds: smog, dioxins and the particulate matter the Nursing College thought was causing those increased rates of childhood asthma. By delaying the requirement that all the Midlothian cement plants install SCR by 2018, the state is turning its back on a problem that Cook Children's hospital described as "an epidemic."

The same is true of SCR in the East Texas coal plants. The technology is being used in other coal plants around the world and in the US to reduce smog pollution. There's no reason it shouldn’t be required for the dirtiest coal plants in Texas that impact DFW air quality. After decades of being out of compliance with the Clean Air Act, DFW is one of the places the technology is needed most.

Last year the Dallas County Medical Society, led by Dr. Robert Haley, petitioned the TCEQ to either close those coal plants or install SCR on them. The doctors' petition was rejected by TCEQ Commissioners and they were told their concerns would be addressed in the DFW air plan. They aren't. Those concerns, along with the proof they presented about the impact of the plants on local air quality, are being ignored.

Electrification of gas compressors is a commonly used technology that could cut smog pollution as well, and yet the TCEQ is not requiring new performance standards that would force operators of hundreds of diesel and gas-powered compressors in North Texas to switch to electricity.

A 2012 Houston Advanced Research Center study found that pollution from a single compressor could raise local ozone levels by as much as 3 to 10 ppb as far away as ten miles. There are at least 647 large compressor stations in the western part of the DFW area. Dallas and other North Texas cities have written ordinances requiring only electric-powered compressors within their city limits based on testimony from industry that electrification was a commonly used technology in the industry. And yet, TCEQ's official position is that electrification isn't feasible.

In ignoring these types of new controls the TCEQ is violating provisions of the Clean Air Act to implement "all reasonably available control technologies and measures" to insure a speedy decrease in ozone levels. Each of these technologies is on the market, being used in their respective industries, and readily available. Studies have shown that each of these technologies could cut ozone levels in DFW significantly, but the TCEQ is refusing to implement them. In doing so, many observers believe it's blatantly in violation of the law.

We don't expect TCEQ to change its position. That well has been poisoned for the foreseeable future. But we do expect a higher standard of enforcement from the Obama Administration EPA. That's why we're asking you to show-up at the public hearing and oppose this dreadful state air plan a week from now in Arlington. We need to demonstrate to the federal government that citizens are concerned about getting cleaner air now, not in the next plan or the one after that. Now. We need to put pressure on the EPA to reject this TCEQ plan, to either send it back to the drawing board or substitute one of its own. Without you showing up, that pressure isn't there.

Between now and Thursday – and all the way through January 30th, you can send prepared comments opposing the TCEQ plan to Austin and the EPA Regional Administrator with a simple click here – and add your own comments as well.

As a reward for coming over and venting your frustration, we'd like you to stay and party with us at the official "retirement party" of State Representative Lon Burnam, beginning at 7:30 pm just four blocks down the street. It's a roasting and toasting of the best friend environmentalists ever had in the Texas Legislature, as well as a fundraiser for Downwinders to continue our work to defend your air. JUST CLICK HERE FOR TICKETS.

Next Thursday you can support clean air two ways in one evening. Help us beat back a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad air plan, and then come celebrate the wonderful, righteous, very good work of a dedicated public servant. See you there.

Maryland: Toxic Air Pollution Top Threat From Fracking

According to a state-sponsored study through the University of Maryland's School of Public Health, "air emissions trump water pollution and drilling-induced earthquakes as a top public health threat posed by future fracking projects in Maryland."

According to a state-sponsored study through the University of Maryland's School of Public Health, "air emissions trump water pollution and drilling-induced earthquakes as a top public health threat posed by future fracking projects in Maryland."

For the better part of a year, faculty surveyed previous research between the gas industry and health effects. They looked at all the possible "exposure pathways" for toxins to reach surrounding populations from gas rigs and facilities and ranked each of the threats. Air quality got a "high" threat ranking, whereas water pollution ranked "moderately high" threat and earthquakes "low."

Dr. Donald Milton, Director of the Maryland Institute for Applied Environmental Health and a UMD professor of epidemiology, biostatistics, and medicine was the study's lead investigator and concluded,

"….existing data show a clear trend: oil and gas activity can spew significant levels of toxic chemicals into the air—and that pollution consistently makes people sick.

"We think [the state] should pay a lot of attention to air pollution," said Milton. Although water pollution is also a concern, Milton told InsideClimate News that there's not enough data on how likely dirty water is to sicken people, nor how strong those health effects would be."

Because most of the reviewed data in the study comes from gas plays that have received a lot of attention over the last couple of years – the Barnett and Eagle Ford in Texas, the Marcellus in Pennsylvania, and the Bakken in North Dakota – Maryland's environmental and public health officials were quick to offer a joint damning disclaimer: "We believe it is important to note that it is largely based on information on natural gas development in areas where the pace of gas development was rapid and intense and without stringent regulations and government oversight." Well yeah, but if our own officials weren't so negligent you wouldn't have the benefit of now learning from our bad examples.

The study was part of a 2011 executive order signed by Maryland Governor Martin O'Malley that outlined a state approach to dealing with potential fracking in the state's western corner, where the Marcellus extends across the Pennsylvania line.

Besides identifying air pollution exposure as a major threat, the study also offered specific recommendations to combat that exposure, including:

– a 2000-foot setback from urban neighborhoods (Dallas and Southlake both have 1500-foot setback provisions)

– baseline air quality monitoring before any drilling or production begins

– constant air monitoring when activity on the site begins

– transparency in the information about the facility.

As the Inside Climate article on the study notes, its conclusions "stand in stark contrast to public concern in heavy-drilling states such as Maryland's neighbor Pennsylvania. Those concerns have tended to focus on tainted water, not air."

Indeed. It's a lot easier to make a fire-breathing water hose into a drive-by YouTube meme than a family gasping for air that won't make them sick. But for most neighbors of urban gas drilling, water quality isn't even on the radar screen because they're getting their H2O from a city pipe running from a lake, not a well. On the other hand, they're directly breathing in the mix of chemicals and pollution coming off the site itself, making their home a frontline toxic hot spot. That site's plume is then combining with hundreds or even thousands of other plumes from similar sites close-by to decrease regional air quality. That air pollution can end-up affecting thousands or millions of residents who don't even live in close proximity to a rig or compressor.

In the most successful "nuisance" court cases against gas operators in the Barnett Shale over the last year or so, air pollution has been the villain keeping families from enjoying their property and running up their medical bills. You can get water trucked in, but it's very hard to do the same with air.

Public comment on the report is open until October 3rd.

Power of the Press: Week after Trib Report on DFW Smog, First “Exceedences” of 1997 Standard

It was only eight days ago the that online Texas Tribune did the first real overview of DFW air quality for this "ozone season." Borrowing heavily from the June 16th Downwinders at Risk presentation to the North Texas regional air quality committee, it concluded that there had been no discernible progress in regional air quality for the past five to six years despite a new state anti-smog plan aimed at getting the area below the 1997 standard of 85 parts per billion.

It was only eight days ago the that online Texas Tribune did the first real overview of DFW air quality for this "ozone season." Borrowing heavily from the June 16th Downwinders at Risk presentation to the North Texas regional air quality committee, it concluded that there had been no discernible progress in regional air quality for the past five to six years despite a new state anti-smog plan aimed at getting the area below the 1997 standard of 85 parts per billion.

Ironically, up to that point, DFW had been enjoying one of the wettest, coolest, most ozone alert-free summers on record. Not one 100 degree day until July and only one "bad air" days of note on June 11th. It looked like we might actually be able to meet the 1997 standard of 85 ppb for the very first time.

That's all changed with this past weeks' return to familiar form. In just seven days, they've been at least four official "ozone alerts" issued for DFW by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Those had produced four "exceedences" of the current 75 parts ppb standard, which the state is now aiming at with another "do nothing" plan under development and due out by the end of the year. On Wednesday the trend got more serious with the addition of the first two "exceedences" of the older 1997 standard we can't seem to conquer – a reading of 88 ppb at the NW Fort Worth monitor at Meacham Field and a 91 at the usually quiet Granbury monitor in Hood County. In the latter case, one mid-afternoon hourly reading reached as high as 113 – just 12ppb short of a violation of an even more ancient standard left over from the 1980's.

For comparison's sake, EPA scientists just sent a letter to EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy recommending that a new, lower federal standard for ozone be set at 60-70 ppb.

It will still take another week of 85 ppb plus days to produce the "fourth highest" readings at the Denton or Keller sites to combine with their 2013 averages and keep DFW in violation of a 17-year old ozone standard. But then again, we have all of August and September to go.

Not surprisingly, two of this summer's hot spots include traditionally troublesome monitors – the Denton and NW Fort Worth site. Tarrant and Denton Counties have historically been the places where the region's highest readings have originated. One reason is wind direction – smog accumulates from upwind sources like the Midlothian cement plants and blows Northwest during the summer. Another more recent reason is the mining of Barnett Shale gas deposits that release huge quantities of smog-forming pollution in the western half of the Metromess, a phenomenon that's been examined in a new UNT study that divided the region's ozone monitors into "Fracking" and "Non-Fracking" areas and found significantly higher readings among those in the Fracking area.

As we went to press with this post, Thursday's readings looked to be producing another round of 75 ppb or higher results. Adding to this year's ozone season irony is that over the last 20 years, July has traditionally been the summer month that produced the fewest number of high ozone readings, book-ended by higher numbers in June and August-September.

Depending on the weather, DFW may still be able to make it over the 1997 standard, 85 ppb hump. But based on this past week's results, that hump just got bigger. Stay tuned.