Zoning

We Did This: A Shingle Mountain Clean-Up is Coming

Despite the flurry of cynical and self-serving photo ops and press releases that Dallas City Hall churned out on Monday celebrating the beginning of a clean-up at Shingle Mountain, no waste was removed from the site yesterday. Nor will any be removed today.

But thanks to you, a clean up is coming. And also thanks to all you, that clean-up is suddenly more concerned with the health of Choate Street residents.

Last week, after a required 30-day public notice period, a state court approved a settlement between the illegal dump’s landowner, the State of Texas and the C ity of Dallas that sets the table for removal of all “above ground” material. On Monday, contractors for the city were installing air monitors around the dump to record the levels of dust created when bulldozers begin loading the estimated 100,000 tons of hazardous waste into waiting 18-wheelers for the half mile trip to the McCommas landfill.

ity of Dallas that sets the table for removal of all “above ground” material. On Monday, contractors for the city were installing air monitors around the dump to record the levels of dust created when bulldozers begin loading the estimated 100,000 tons of hazardous waste into waiting 18-wheelers for the half mile trip to the McCommas landfill.

According to a separate agreement between the City and the landowner, the City has until December 25th to “begin” the removal process, i.e. sending trucks to actually haul off waste.

This result was anything but a foregone conclusion when the “Move the Mountain” campaign began last August 5th with a new conference at City Hall demanding the illegal dump be gone by the end of the year.

Only 4 months ago City Hall hadn’t made any commitments to a clean-up and had no estimate for when one would take place. The City Council had just unanimously rejected pleas from Choate Street residents to re-establish the Environmental Health Commission as part of a new Climate Plan. We were at a low ebb in our campaign.

But a strategic and constant barrage of public protest and shaming – mock trials, leafleting the Mayor’s law firm,  dumping waste at City Hall – along with the attendant embarrassing media coverage, made the City of Dallas actually commit itself to a clean-up it hadn’t planned on doing quite as fast, if at all.

dumping waste at City Hall – along with the attendant embarrassing media coverage, made the City of Dallas actually commit itself to a clean-up it hadn’t planned on doing quite as fast, if at all.

Keeping constant pressure applied for four months was often exhausting, but momentum grew with each new demonstration. November 16th might have seen “peak” Shingle Mountain coverage with publication of a long and well-written expose in the Washington Post, a public demonstration at the dump’s gate counting down the days until a clean-up was supposed to begin and a crew from Solodad OBrien’s upcoming BET documentary in town to film it for a premiere in February.

Thanks to everyone who showed up to those demonstrations of support. Whether you attended one or all of them, your presence made a difference.

Thanks to everyone who showed up to those demonstrations of support. Whether you attended one or all of them, your presence made a difference.

Those of you who sent in public comments this last month also had an impact. Initially, neither the State nor City expressed the least bit of concern about the health of Choate Street residents during the messy business of removing the waste. No specific provisions for controlling dust or monitoring air quality were included in the City agreement or State settlement.

But after over 50 letters and emails worth of comments were sent and included in the public record, the City suddenly got religion. It included dust control measures and air monitoring in its final description of the clean-up to the court. Lawyers for Marsha Jackson, Co-Chair of Southern Sector Rising, and a Downwinder board member cited your public comments as the reason the City included these new safeguards at the last minute. So congratulations a second time.

Now what?

The settlement and agreements signed by the State and City are vague about what happens after the land surface is cleared of waste. Will there be any monitoring wells drilled to see if contamination seeped into the groundwater? Will the clean-up extend below the ground as well as above if the soil is contaminated? If pollution is found in the soil or water, what level of contamination is “acceptable”, i.e. what are the clean-up levels then?

And what and who will be responsible for the health costs -financial and physiological – accumulated by Ms. Jackson and the other Choate Street families?

Residents have drafted their own neighborhood plan for redevelopment that drastically changes the zoning in their community. They’ve submitted it to City Hall. But the same City Council Member that was taking unearned credit for Shingle Mountain’s removal on Monday is fighting this neighborhood plan tooth and nail.

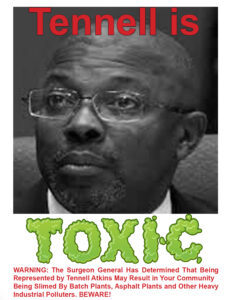

District 8 City Council Member  Tennell Atkins is one of the biggest reasons Shingle Mountain exists at all, and why its removal has been so delayed. He’s been nothing but an obstacle to be overcome instead of an ally for his constituents. Adding insult to injury, he’s now standing in the way of Choate Street and Flora Farms residents being able to rebuild their community from the devastation he’s inflicted on them.

Tennell Atkins is one of the biggest reasons Shingle Mountain exists at all, and why its removal has been so delayed. He’s been nothing but an obstacle to be overcome instead of an ally for his constituents. Adding insult to injury, he’s now standing in the way of Choate Street and Flora Farms residents being able to rebuild their community from the devastation he’s inflicted on them.

Atkins is up for re-election in May and it’s our hope that all of you who made this Shingle Mountain clean-up happen will stick around and finish the job by helping us remove this political tumor that threatens the future of Southern Dallas.

Sunday December 13th was the two-year anniversary of the very first Robert Wilonsky column about Shingle Mountain in the Dallas Morning News. Some of us believed that first column would expose the problem and move officials to act to resolve it. 13 Wilonsky Shingle Mountain columns later, we’re still waiting on the trucks that should have arrived in January 2019.

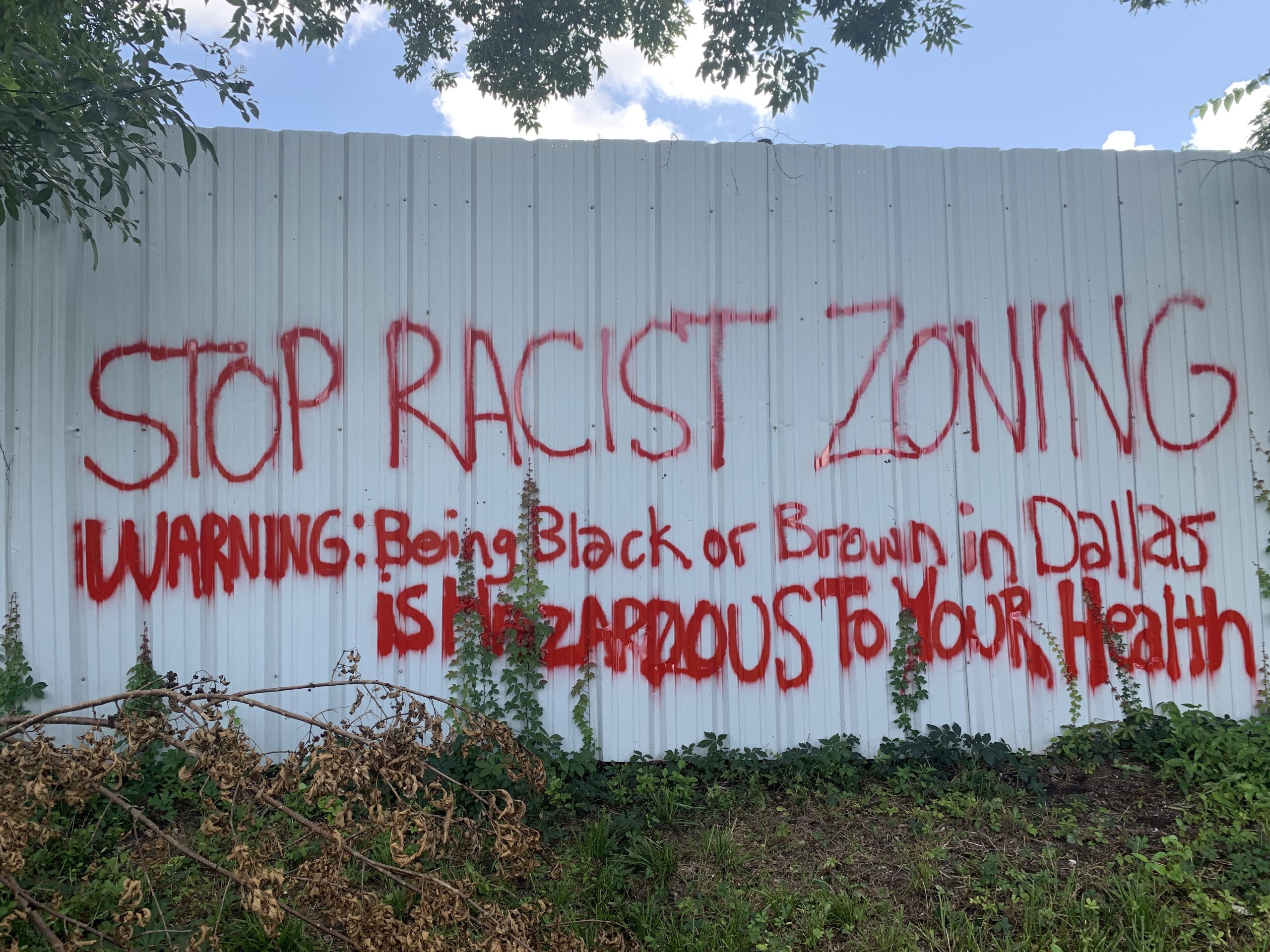

If they show up before Christmas Day , it will be one of the best, most satisfying moments of a terrible year. But it won’t be the end of the struggle over racist zoning that began on Choate Street. That struggle is just beginning.

National Fund Spotlights Downwinders’ Efforts to “Take Back Our Cities”

Today, the Peace Development Fund is using its national presence and contacts to help raise funding for Downwinders at Risk, under the banner of “Taking Back our Cities.”

We’re being featured on their website all day. We’re one of only 13 groups chosen to receive this kind of attention from the Fund.

The Fund liked our work around the upcoming Dallas MasterPlan process, partnering with Southern Sector rising and neighborhood groups to rezone Southern Dallas communities tract-by-tract to improve environmental health.

We’re one of the few environmental groups in the country using land use planning tools to reduce residents’ exposure to pollution. Our aim is to dismantle the racism institutionalized in local zoning codes that have forced People of Color and industry to live side-by-side for decades.

Many of you helped us reach our Giving Day goal. But we need those of you who didn’t contribute on Giving Day to do your part today. Here’s your chance to join the fight for cleaner air and environmental justice.

Thanks.

Director

____________________________________

COVID Connects:

Racist Zoning

to

Increased Vulnerability to COVID

What is It?

For most people, “zoning” isn’t a very interesting topic. How your property is classified by city government is of little concern – until you discover how few protections you have or how close a large polluter can operate near you.

In Dallas as well as most American cities, People of Color have been historically forced by law or practice to live in neighborhoods they had to share with industry. The Trinity River floodplains were used as a large dumping ground for both people and factories deemed “undesirable” by white power brokers.

In Dallas as well as most American cities, People of Color have been historically forced by law or practice to live in neighborhoods they had to share with industry. The Trinity River floodplains were used as a large dumping ground for both people and factories deemed “undesirable” by white power brokers.

While illegal now, that institutionalized discrimination lives on in the form of obsolete racist zoning that still makes Southern Dallas a dumping ground.

Why Do It?

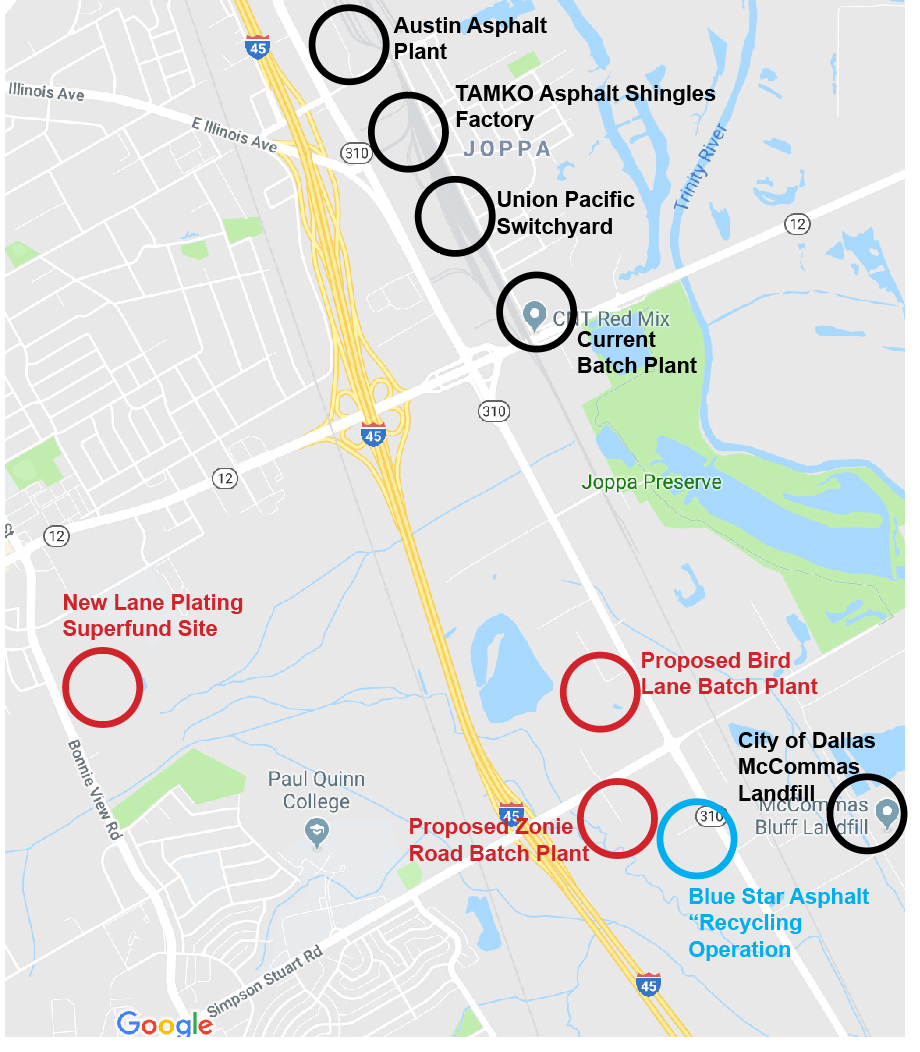

Unless you change the zoning classifications in South Dallas that make it such a haven for dirty industry, the City’s pollution burden will remain concentrated there, stifling economic development and quality of life. During the last two years Southern Dallas has fought off four proposed batch plants in the same neighborhood because the zoning directs them there. The notorious Shingle Mountain illegal dump took advantage of zoning loopholes to withhold notification of its activities from its neighbors. Instead of playing “whack-a-mole” and having to organize anew against every attempt to site a new polluter there, Southern Dallas residents need to re-write the leftover racist zoning laws and prohibit their part of town from becoming the default Big D dumping ground.

During the last two years Southern Dallas has fought off four proposed batch plants in the same neighborhood because the zoning directs them there. The notorious Shingle Mountain illegal dump took advantage of zoning loopholes to withhold notification of its activities from its neighbors. Instead of playing “whack-a-mole” and having to organize anew against every attempt to site a new polluter there, Southern Dallas residents need to re-write the leftover racist zoning laws and prohibit their part of town from becoming the default Big D dumping ground.

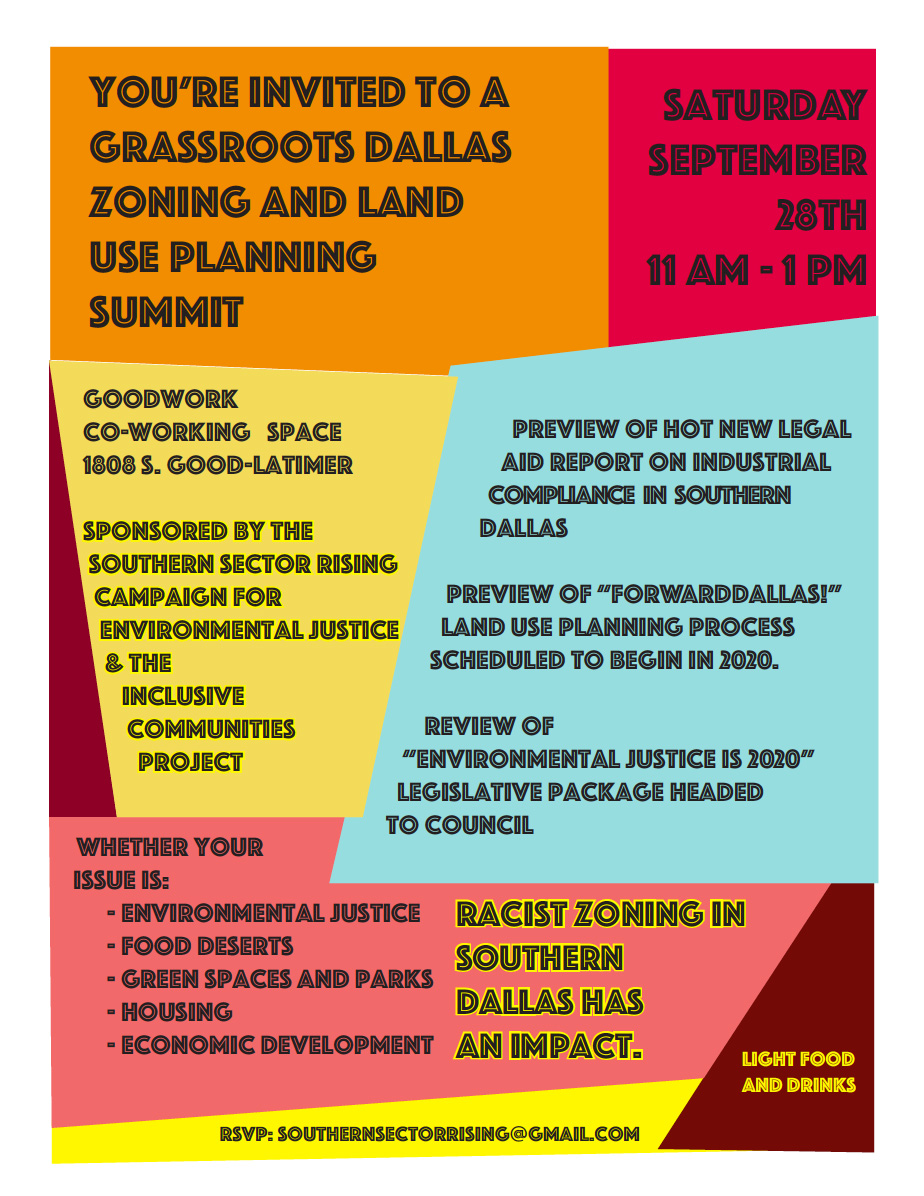

Downwinders is partnering with our friends at Southern Sector Rising and the Inclusive Communities Project to do just that. Dallas is gearing up for a once-in-a-decade review of the City’s MasterPlan that will invite residents to imagine how they want to change their neighborhoods. There’s an opportunity to submit new plans that reverse the racist zoning that plagues the entire Southern part of Dallas.

We’re working with specific Southern Dallas neighborhoods that want to give residents more green space, more buffer zones between themselves and pollution, and even begin proceedings to remove industry from their communities. It’s a 2-3 year process but the end result is increased Environmental Justice in places that desperately need it.

What’s the COVID

Connection?

Bottom: COVID Risk Factors

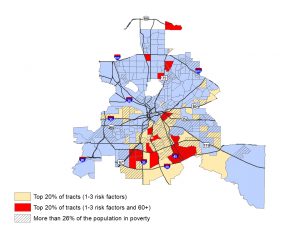

Research done during this pandemic shows Black and Brown residents are being disproportionatey impacted by the COVIC virus.This is being attributed to a number of “pre-existing conditions” in the neighborhoods where they live, including lack of health insurance and health care facilities, poverty and…exposure to air pollution. We know that Black and Brown residents are more likely to be exposed to more and higher levels of air pollution than their white peers.

Research done during this pandemic shows Black and Brown residents are being disproportionatey impacted by the COVIC virus.This is being attributed to a number of “pre-existing conditions” in the neighborhoods where they live, including lack of health insurance and health care facilities, poverty and…exposure to air pollution. We know that Black and Brown residents are more likely to be exposed to more and higher levels of air pollution than their white peers. If you change the zoning so that Southern Dallas residents are not living side-by-side with polluters, you reduce their exposure to poisons and improve public health, including making them less vulnerable to viruses like COVID.

If you change the zoning so that Southern Dallas residents are not living side-by-side with polluters, you reduce their exposure to poisons and improve public health, including making them less vulnerable to viruses like COVID.

STATUS?

“forwardDallas!” is the name of the process the City of Dallas is using to redraw its MasterPlan. It was supposed to begin this Spring but may not start until summer. It will involve lots and lots of neighborhood meetings.Downwinders, Southern Sector Rising and the Inclusive  Communities Project isn’t waiting however. We’ve already met with residents’ groups in the Floral Farms and Fruitdale neighborhoods to begin a grassroots planning process. Because of their preparation, these groups will be able to show up to the City meetings with their own plans already developed and ready to be approved. More online meetings are being scheduled for other neighborhoods.

Communities Project isn’t waiting however. We’ve already met with residents’ groups in the Floral Farms and Fruitdale neighborhoods to begin a grassroots planning process. Because of their preparation, these groups will be able to show up to the City meetings with their own plans already developed and ready to be approved. More online meetings are being scheduled for other neighborhoods.

No group has used the “forwardDallas” process to overhaul Dallas zoning in such a comprehensive way. No coordinated effort has ever been focused on this mission. Like so many projects Downwinders takes on, its a “first.” But it’s a chance to make fundamental Change.

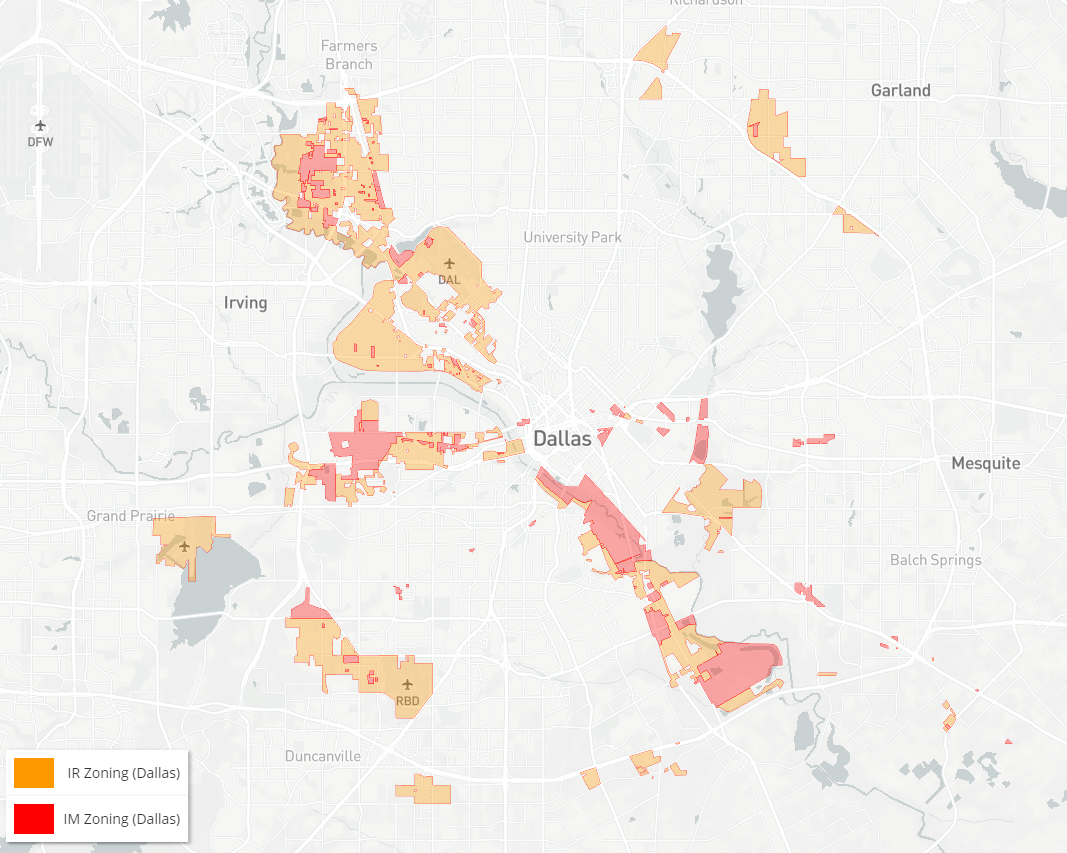

This obsolete pattern of “redlining” and segregation lives on in a legacy of racist zoning that still drives polluters to Southern Dallas and along the Trinity River Corridor. Most of the land set aside for heavy industry in Dallas is still south of the River – in predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods like West Dallas and Joppa.

To make sure Southern Dallas doesn’t remain the City’s dumping ground you have to change the zoning that controls what can go where and next to whom.

The Only Thing Missing in Dallas’ Climate Plan “Focus on Equity” is…any measure of Equity

A staff presentation focusing on Dallas environmental equity lacks any metrics for comparing residential pollution burdens, or even for measuring the success of its own outreach effort.

So how does City Hall know what environmental “equity” looks like?

According to management guru Peter Drucker, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.”

Then what does it mean that a full year into a Dallas climate planning process heavily touted as reflecting the city’s emphasis on “equity” there’s still no map showing how pollution burdens are distributed across Big D? And what does it tell you when a presentation meant to advertise the inclusiveness of the City’s outreach effort for its climate plan doesn’t document participation by residents of color?

It tells you that despite all the rhetoric on the subject, Dallas City Hall isn’t serious about environmental justice yet.

Office of Environmental Quality and Sustainability Susan Alvarez presents the City’s climate plan through “an equity lens.”

Exhibit A: “Dallas’ Climate Action Through an Equity Lens.”

This was a presentation that Susan Alvarez, Assistant Director of the City of Dallas Office of Environmental Quality & Sustainability, gave as part of Eastfield College’s Sustainability as a Social Justice Practice: Developing Resilient Strategies held last Friday, November 8th.

Context is everything and so it’s important to note that the entire thrust of both the Conference and the City’s specific presentation was aimed squarely at how to respond to current environmental challenges in an equitable and just way. Here was a chance for Dallas OEQS city staff to display their embrace of equity as it relates to the climate plan it’s been paying a half-million dollars to consultants to construct. It was their very own EJ report card.

Equity and the Climate Plan:

And sure enough, there was no turning away from Dallas’ racist history in Alvarez’ presentation. Maps showing the City’s chronic segregation and poverty were included, as well as allusions to the Trinity River as the city’s dividing line between Haves and Have-Nots. Alvarez spoke about the current “Redlining Dallas” exhibit at City Hall that traces the City’s history of racism across 50 feet of photographs and stories.

In fact, just about every impact of the City’s official segregation was referenced, except for the one you’d expect.

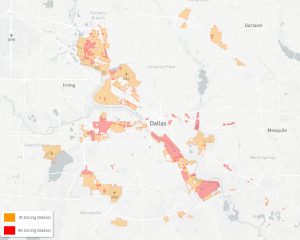

There was not a single slide or sentence expended on the disproportional environmental impacts of 100 years or more of Dallas racism. No maps of where heavy industry zoning is allowed in the City. No maps of where most of the City’s largest polluters are located. No maps of what zip codes or Council Districts have the highest pollution per capita numbers. No references to past environmental justice struggles with the City like the West Dallas RSR fight, or gas drilling.

Watching the presentation you’d get the impression that racism infected every aspect of life for Dallas residents of color except for their exposure to pollution. But of course, we know that’s not true.

During this and other presentations on the climate plan-in-progress, staff go out of their way to point out that industry makes up “only 8% of emissions.” But if you’re interested in applying “equity” to this number the next slide should show the audience where that industry is distributed in Dallas – a map showing you where industrial polluters are allowed to set-up shop. A slide to show you the amounts of permitted pollution by Zip Code, or maybe actual 2017-18 emissions by Council District. But there is no next slide.

If there were, it would show that most of that industry is located in predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods. Racist zoning is at the heart of not just banking, education, and employment inequities in Dallas. It also means the dirtiest industries have always been located in close proximity to people who were institutionally considered Second-Class citizens.

This one slide is already more information on Dallas environmental equity than you’ll find in the entire City staff presentation on equity and the climate plan

Disproportional exposure to industrial pollution by residents of color is not just AN equity issue. It’s THE single most important equity issue when you’re speaking about environmental justice in Dallas. The City’s Black and Brown residents are more likely to be exposed to harmful pollution than their white peers because the City’s own zoning designed it that way – but you’d never know it watching this presentation, on equity, at the social justice conference.

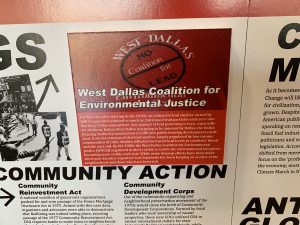

The “Redlining Dallas” exhibit that Alvarez cited thinks so. Along with other insidious effects of racism, it gives space to the RSR clean-up fight Luis Sepulveda and his West Dallas Coalition for Environmental Justice waged in the early 1990’s. But there was no mention of that fight or any other Dallas examples during the presentation on equity, at the social justice conference.

Staff referenced every other kind of red-lining on display at the City Hall exhibit – except the one most relevant to the topic.

Nor was there any mention of how much industry was located in the Trinity River floodplain, doing business in Black and Brown neighborhoods founded because the City wouldn’t allow these so-called “undesirables” to live anywhere else but side by side with “undesirable” industries. Alvarez made the point in the presentation that climate change means more flooding in general and more severe flooding. The next slide should show who and what is affected by that new flooding risk. A slide showing what percentage of heavy industry is located in the flood plain. A slide showing what the racial make-up and income levels are of those who’ll be more affected by increased flooding…and contamination. But there was no next slide, in the presentation on equity, at the social justice conference.

If you don’t have accurate maps of the inequities plaguing the status quo, how do you know when or if you’re ever getting rid of them? How do you judge success without a baseline?

PR, Process and Equity:“I don’t think it’s important to say I’ve got four black people in my stakeholders group.”

Alvarez lowered expectations for the presentation by saying it would only look at the question of equity in how it was applied to the City’s climate plan “community engagement.” No actual equity policy options from other plans were on the table, just how well the plan’s public relations campaign did.

Not very well, she admitted. In fact the initial meetings and publicity were so anemic that she said the professional PR folks at Earth X had a come-to-Jesus-meeting with staff about a reboot. So that’s tens of thousands of dollars wasted on PR consultants only to be usurped by better free advice from locals.

A meeting of the Dallas climate plan advisory group.

In her recounting of the climate plan’s PR rollout and planning process Alvarez gave an overview of the mechanics. “X” number of meetings attracted “X” numbers of people. The City’s survey got “X” number of responses. An “X” number of people serve on an advisory stakeholders group.

Considering the very specific circumstances of the presentation, the next slide should have been how the results of those attending meetings, or completing a surveys, or advisory committee memberships reflect Dallas’ population as a whole. How do we stack up to who we’re representing? According to the Statistical Atlas Dallas is approximately 25% Black, 41% Hispanic , 30% White and 3% Asian. So the next slide should compare what percentage of those attending climate plan meetings, or completing surveys, or becoming advisory committee members were Dallas residents of color vs the city demographics.

But there was no next slide about how inclusive the City’s climate plan community outreach or advisory process has been in the presentation on equity, at the social justice conference.

In response to a question about the lack of such information Alvarez said it was irrelevant to the topic at hand. “I don’t think it’s important to say I’ve got four black people in my stakeholders group.”

Since the advisory group membership is only listed online by organizational affiliation it’s impossible for anyone outside the meetings to know what the ethnic or gender make-up of it is. There are 39 separate entities listed. 25% of that number would be nine to ten black people.

In elaborating, Alvarez challenged the idea that mapping Dallas’ racial or ethnic disparities in pollution  burdens was necessary to understanding “Dallas’ Climate Action Through an Equity Lens.” She more or less stated it didn’t matter. (the presentation was recorded by Eastfield College and Downwinders has asked for access to it in order to quote Alvarez accurately).

burdens was necessary to understanding “Dallas’ Climate Action Through an Equity Lens.” She more or less stated it didn’t matter. (the presentation was recorded by Eastfield College and Downwinders has asked for access to it in order to quote Alvarez accurately).

Nothing could better summarize the kind of Catch-22 “don’t confuse me with the facts” approach to “equity” the City staff has taken in regards to environmental racism than the belief that actual data about Dallas environmental racism is of no use to the study or remedying of Dallas’ environmental racism.

And nothing makes a better case for the need to pass environmental justice reforms the Southern Sector Rising Campaign is advocating at Dallas City Hall, including an environmental justice provision in Dallas’ economic development policy, restoration of the Environmental Health Commission, and creation of a Joppa Environmental Preservation District. If residents want environmental equity considered in city policy they’re going to have to enlist their City Council members, do it themselves, and enact reforms like these.

The same is true as City Hall ramps up to take on citywide land-use planning in its “forwardDallas!” process early next year. When staff recently released the City’s “equity indicators” report, there was an indicator for everything but the environment. It only reinforced the idea that the environment, and environmental justice, are still after-thoughts in Dallas city government. Residents will have to arm themselves with the information the City staff can’t or won’t provide. They should start with the recent Legal Aid report “In Plain Sight” that demonstrates deep neglect for code and zoning regulations in Southern Dallas.

And it also goes for the climate plan. Southern Sector Rising’s first recommendation for the city’s climate plan last May was “Remove industrial hazards from the flood plain.” On the other hand, the idea of land use reforms in the floodplain hasn’t appeared in any official literature or presentation associated with the city’s climate plan.

Grist recently published an article about the Providence Rhode Island climate planning process that looks to be the exact opposite of the model Dallas has adopted. But that city benefited from having an environmental justice infrastructure already in place when the climate crisis assignment arrived. Where’s the home for Environmental Justice in Dallas City Hall? Right now, it’s with staff that doesn’t think metrics about equity are important, in its presentation on equity, at the social justice conference.

Listen to Our New Chair Get Interviewed By D Magazine

Downwinders at Risk’s new Chair Evelyn Mayo gets a huge shout out in D magazine’s popular online manifestation with her very own “Earburner” podcast.

D magazine reporter Matt Goodman and D Managing Editor Tim Rogers interview Evy about her new report on Southern Dallas zoning for Legal Aid, her Roller Derby years in Singapore, and of course, Particulate Matter.

CLICK HERE to link to the podcast and learn more about one the new dynamic leaders of Downwinders at Risk.