Shingle Mountain

Downwinders Chair is one of D’s 78 Women Making Dallas Great

D Magazine selected “78 Women Who Make Dallas Great” to profile in its September issue. Proud to say 26-year old Downwinders at Risk Chair Evelyn Mayo is one of them.

Meet the new Downwinders at Risk

Dallas Morning News Consumer Watchdog columnist Dave Lieber found himself listening in on the annual “State of the Air” presentation we’re always invited to give at the Arlington Conservation Council. Lots of information about smog and PM pollution but what really got his attention was the description in the Q&A about the wholesale transformation of Downwinders’ mission and board since 2017. He was so impressed he decided to write about it for his next column. Here’s the flattering result with some great pics our Chair Evelyn Mayo, our founder Sue Pope and (almost) our complete board as of August 2021. Thanks to Dave for the coverage and to all of you for supporting us through this transition.

For those without a DMN subscription we’re reprinting the entire article below:

Top anti-pollution group gets a makeover to an all-women board with young adults and people of color

Most nonprofit boards can only dream of bringing in younger members and people of color to reflect their communities. This one did it.

The phrase “trophy wall” caught my attention.

Jim Schermbeck, the wise old battler against Dallas-Fort Worth air pollution for the last quarter century, was bragging about his group’s new generation of leadership and its new focus on protecting neighborhoods.

I was in a webinar listening to Schermbeck, program director for pollution fighter Downwinders at Risk, as he gave an overview of our air quality (it’s bad!) when the trophy wall thing perked me up. It had something to do with Dallas City Hall officials leaving their jobs. Forgive the gruesome image, but the symbolism was that their heads were hung up on a wall.

I turned up the volume on my computer so I could hear.

He told a story about how the city of Dallas in recent years had allowed two northern Dallas neighborhoods to create their own land use plans. But when two southern Dallas neighborhoods tried to do the same, they were told by the city that neighborhood-based land use plans created by community members were no longer acceptable.

Putting it bluntly, white neighborhoods were allowed to create bottom-up plans that were presented to and accepted by city officials. But these neighborhoods where people of color live were forced to accept top-down plans imposed upon them by City Hall.

Schermbeck mentioned the group’s chair, Evelyn Mayo, a 26-year-old firebrand, and said, “This made her mad.”

Mayo helped organize several groups into the Coalition for Neighborhood Self-Determination, which agitated for fairness in community-created land use plans. Letters were sent to Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson, the City Council and City Manager T.C. Broadnax.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/dmn/VHF2H4PGCBFPHDLIWRBDDDUSFU.jpg)

The power play appears to have worked. Three zoning officials decided to retire from the city. They are: Peer Chacko, the city’s director of planning and urban design; David Cossum, development services administrator; and assistant zoning director Neva Dean.

Kris Sweckard, the director of sustainable development and construction, was reassigned to the city’s aviation department on an interim basis.

“So at age 26, this woman has a department head on her trophy wall for a good cause,” Schermbeck was saying. “It’s just amazing to watch. If you ever think young people are not with it, and you want to build your confidence back up about people, please come to a board meeting or hang out with Evelyn and her friends for a while. They will restore your confidence about where we’re headed. She’s an amazing person, and our board is really great.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/dmn/A2SOKXOTI5HBBAGB6CVHNDCLJA.jpg)

Shine a spotlight

I asked Mayo how she felt about the trophy wall analogy. “I don’t think it’s something you should aspire to,” she said. “We were simply reacting to circumstances presented before us.”

Later, she toughened it up a bit, saying: “Whether it’s a trophy wall or not, what’s happening at City Hall is a product of their own incompetence.”

Downwinders board member Misti O’Quinn told me that the coalition shined a spotlight on one portion of neighborhood zoning, and when you shine a spotlight you can expose. What does that mean for city officials? “You take away their sense of security,” she said.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/dmn/XOB66IBJRFCCPDQFPUCP7KZPLA.jpg)

I attempted to reach the four City Hall officials but was unsuccessful. When I ran this scenario up the flagpole to Broadnax, he provided a written statement to The Watchdog explaining that when several staffers announced their intention to retire this year, it presented an opportunity to realign their departments.

“Over the next several months,” he said, “we intend to simultaneously restructure permitting and planning and realign the departments and leadership that oversee them. Reorganizing these departments will maximize effectiveness and productivity.”

He made no mention of the coalition or its agitation.

Change with the times

This story runs far deeper than citizen agitation. Downwinders represents a model for how environmental and other nonprofits can alter their profile, their mission and their leadership.

As I looked at the group’s history, I saw how Downwinders has changed in recent years.

Formed in 1994 by Midlothian rancher Sue Pope and other rural residents and suburbanites, Downwinders’ mission for the longest time was fighting pollution caused by cement plants.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/dmn/YOOOOF4INFGW5JU7KCBDVI6NUQ.JPG)

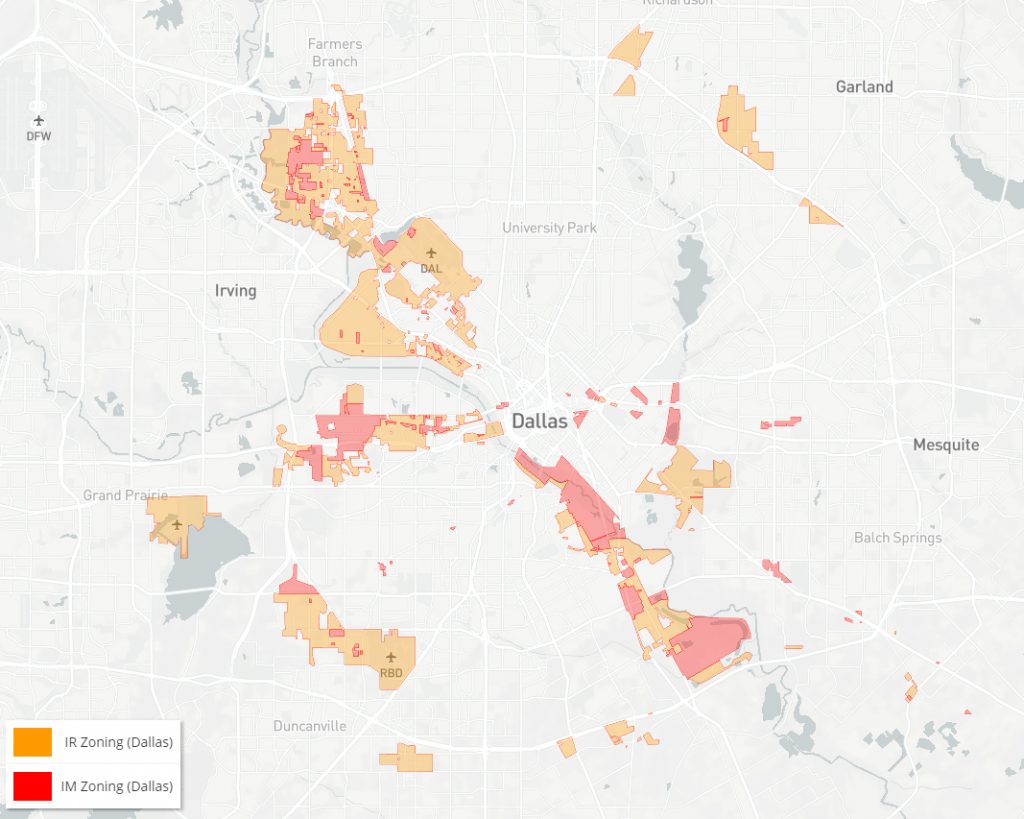

But by 2017, the year Mayo joined the board, it was becoming clear — thanks in part to the hideous Shingle Mountain dump site in southeast Oak Cliff — that Dallas needed a spotlight to focus on what activists and academics call historically racist zoning. That’s what allows dirty industries into poorer residential neighborhoods where people of color live. Correcting those inequities is called environmental justice.

In the next two years, the old guard board members, many of whom had served since the group’s creation, all dropped off. The board and its mission changed from rural/suburban to urban.

“It was very traumatic,” Schermbeck recalls. “But I’m so glad we did it because we’re more plugged in than ever before.”

Mayo says the worst moment came in 2019 when she was elected to the unpaid job of chair in what she calls “a somewhat contentious vote.”

The board is now all women; two are Asian-American, five are Black, two are Latina and three are white. Three members are in their 20s, and six are in their 30s. One member is 17 years old.

Most community nonprofits, especially in the traditional environmental arena, can only dream of putting together a board with that diversity.

Mayo, who teaches at Paul Quinn College, has a perfect resume for her leadership role. She majored in environmental science in college with a focus on race and ethnicity.

Working as a paralegal at Legal Aid of NorthWest Texas, she co-authored a study called “In Plain Sight,” which examined the governmental failures that allowed a disaster like Shingle Mountain to spiral out of control.

Then while teaching undergraduates at Paul Quinn, she and her students in 2020 completed a study – “Poisoned by Zip Code: An Assessment of Dallas’ Air Pollution Burden by Neighborhood.” You can guess the results of that survey.

The Downwinders’ main goal, in addition to continuing its legacy battle against dirty air, is to bring power and expertise to the city’s poorer neighborhoods that have had no say in dirty industries moving in.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/dmn/3VRLM7INOFGSHGAAN667IY3NYI.jpg)

“The legacy of racist zoning perpetuates unless you fundamentally redraw the map through these land use plans,” she says. “People who are affected must be involved in the decision-making process about what their neighborhood will look like. This will probably have better outcomes for their health and wellness.”

Yet, she adds, “People who live there and bear the brunt of the pollution are still not at the decision-making table.”

Mayo says her group needs all the help it can get.

“No matter who you are, we can put you to work if you’re interested and willing,” she says.

Note: A tip of The Watchdog’s hat to Downwinders’ board members: Cressanda Allen; Satavia Hopkins; Misti O’Quinn; Essence Tetteh; Marsha Jackson; Cindy Hua; Amber Wang; Idania Carranza; Soraya Coli; Amanda Poland; Michelle McAdam; and Shannon Vorpahl.

We Did This: A Shingle Mountain Clean-Up is Coming

Despite the flurry of cynical and self-serving photo ops and press releases that Dallas City Hall churned out on Monday celebrating the beginning of a clean-up at Shingle Mountain, no waste was removed from the site yesterday. Nor will any be removed today.

But thanks to you, a clean up is coming. And also thanks to all you, that clean-up is suddenly more concerned with the health of Choate Street residents.

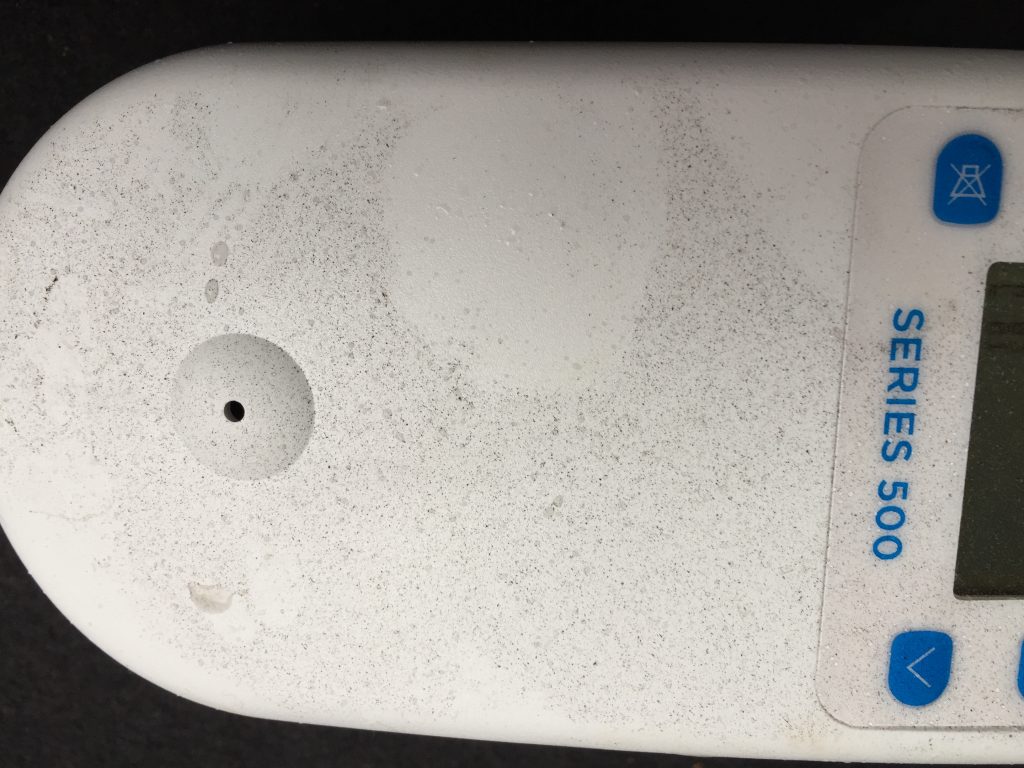

Last week, after a required 30-day public notice period, a state court approved a settlement between the illegal dump’s landowner, the State of Texas and the C ity of Dallas that sets the table for removal of all “above ground” material. On Monday, contractors for the city were installing air monitors around the dump to record the levels of dust created when bulldozers begin loading the estimated 100,000 tons of hazardous waste into waiting 18-wheelers for the half mile trip to the McCommas landfill.

ity of Dallas that sets the table for removal of all “above ground” material. On Monday, contractors for the city were installing air monitors around the dump to record the levels of dust created when bulldozers begin loading the estimated 100,000 tons of hazardous waste into waiting 18-wheelers for the half mile trip to the McCommas landfill.

According to a separate agreement between the City and the landowner, the City has until December 25th to “begin” the removal process, i.e. sending trucks to actually haul off waste.

This result was anything but a foregone conclusion when the “Move the Mountain” campaign began last August 5th with a new conference at City Hall demanding the illegal dump be gone by the end of the year.

Only 4 months ago City Hall hadn’t made any commitments to a clean-up and had no estimate for when one would take place. The City Council had just unanimously rejected pleas from Choate Street residents to re-establish the Environmental Health Commission as part of a new Climate Plan. We were at a low ebb in our campaign.

But a strategic and constant barrage of public protest and shaming – mock trials, leafleting the Mayor’s law firm,  dumping waste at City Hall – along with the attendant embarrassing media coverage, made the City of Dallas actually commit itself to a clean-up it hadn’t planned on doing quite as fast, if at all.

dumping waste at City Hall – along with the attendant embarrassing media coverage, made the City of Dallas actually commit itself to a clean-up it hadn’t planned on doing quite as fast, if at all.

Keeping constant pressure applied for four months was often exhausting, but momentum grew with each new demonstration. November 16th might have seen “peak” Shingle Mountain coverage with publication of a long and well-written expose in the Washington Post, a public demonstration at the dump’s gate counting down the days until a clean-up was supposed to begin and a crew from Solodad OBrien’s upcoming BET documentary in town to film it for a premiere in February.

Thanks to everyone who showed up to those demonstrations of support. Whether you attended one or all of them, your presence made a difference.

Thanks to everyone who showed up to those demonstrations of support. Whether you attended one or all of them, your presence made a difference.

Those of you who sent in public comments this last month also had an impact. Initially, neither the State nor City expressed the least bit of concern about the health of Choate Street residents during the messy business of removing the waste. No specific provisions for controlling dust or monitoring air quality were included in the City agreement or State settlement.

But after over 50 letters and emails worth of comments were sent and included in the public record, the City suddenly got religion. It included dust control measures and air monitoring in its final description of the clean-up to the court. Lawyers for Marsha Jackson, Co-Chair of Southern Sector Rising, and a Downwinder board member cited your public comments as the reason the City included these new safeguards at the last minute. So congratulations a second time.

Now what?

The settlement and agreements signed by the State and City are vague about what happens after the land surface is cleared of waste. Will there be any monitoring wells drilled to see if contamination seeped into the groundwater? Will the clean-up extend below the ground as well as above if the soil is contaminated? If pollution is found in the soil or water, what level of contamination is “acceptable”, i.e. what are the clean-up levels then?

And what and who will be responsible for the health costs -financial and physiological – accumulated by Ms. Jackson and the other Choate Street families?

Residents have drafted their own neighborhood plan for redevelopment that drastically changes the zoning in their community. They’ve submitted it to City Hall. But the same City Council Member that was taking unearned credit for Shingle Mountain’s removal on Monday is fighting this neighborhood plan tooth and nail.

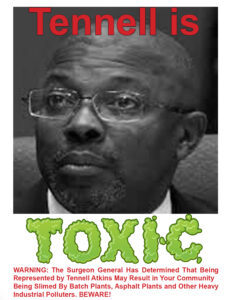

District 8 City Council Member  Tennell Atkins is one of the biggest reasons Shingle Mountain exists at all, and why its removal has been so delayed. He’s been nothing but an obstacle to be overcome instead of an ally for his constituents. Adding insult to injury, he’s now standing in the way of Choate Street and Flora Farms residents being able to rebuild their community from the devastation he’s inflicted on them.

Tennell Atkins is one of the biggest reasons Shingle Mountain exists at all, and why its removal has been so delayed. He’s been nothing but an obstacle to be overcome instead of an ally for his constituents. Adding insult to injury, he’s now standing in the way of Choate Street and Flora Farms residents being able to rebuild their community from the devastation he’s inflicted on them.

Atkins is up for re-election in May and it’s our hope that all of you who made this Shingle Mountain clean-up happen will stick around and finish the job by helping us remove this political tumor that threatens the future of Southern Dallas.

Sunday December 13th was the two-year anniversary of the very first Robert Wilonsky column about Shingle Mountain in the Dallas Morning News. Some of us believed that first column would expose the problem and move officials to act to resolve it. 13 Wilonsky Shingle Mountain columns later, we’re still waiting on the trucks that should have arrived in January 2019.

If they show up before Christmas Day , it will be one of the best, most satisfying moments of a terrible year. But it won’t be the end of the struggle over racist zoning that began on Choate Street. That struggle is just beginning.

Send Your Public Comments for a SAFE Shingle Mountain Clean-Up

What:

Public Comments on the State’s Settlement with Shingle Mountain landowner

When:

Now thru Sunday, Dec 6th

How:

Use our ClickNSend email feature to send your comments to Texas Attorney General’s office in 90 seconds

Why:

To make sure residents’ health is protected during a Shingle Mountain clean-up

A four-month citizens’ campaign pressuring the City of Dallas to clean-up the Shingle Mountain illegal dump in Southern Dallas by the end of 2020 is on the verge of paying off.

Following a pattern that began in summer, on the very same October day groups planning civil disobedience at the dump site announced another action, the City signed an agreement with the Shingle Mountain landowner to take responsibility to “begin” a clean-up by Dec 25th. In return, the City received a check for $1 million from the landowner.

Meanwhile, the state has also reached an agreement with the landowner that clears the way for a clean-up. That agreement is now up for public comment until 12 Midnight Sunday, December 5th.

You can help us protect the health of the Choate Street families most affected by the clean-up by providing your public comments to this State agreement. Doing so sends a message to both Austin and Dallas City Hall that they’re being held accountable now that they’ve been put in charge of removing the 100,000 tons of illegal hazardous waste they helped create.

Public pressure is what’s brought us to this point. Public pressure must now  make sure the clean-up itself won’t increase residents’ exposure to hazardous materials like Silica, Formaldehyde, Petroleum By-Products and exotic glues and adhesives used to make shingles that are now crumbling into tons of microscopic particles.

make sure the clean-up itself won’t increase residents’ exposure to hazardous materials like Silica, Formaldehyde, Petroleum By-Products and exotic glues and adhesives used to make shingles that are now crumbling into tons of microscopic particles.

On Monday November 16th, members of Southern Sector Rising, Downwinders at Risk, Southern Dallas Shingle Movers and other protesters gathered at the d ump’s front gate for an action that hoisted and hooked a huge Clean-Up Countdown Calendar onto the eight-foot-tall metal fence that divides the site from South Central Expressway.

ump’s front gate for an action that hoisted and hooked a huge Clean-Up Countdown Calendar onto the eight-foot-tall metal fence that divides the site from South Central Expressway.

Designed as a giant-size desk calendar, it marked the 30 days of public notice ending on Sunday the 6th. Rev. Frederick Haynes of Friendship-West Baptist Church, Rabbi Nancy Kasten, and the Rev. Amy Moore joined Marsha Jackson and her neighbo rs in speaking about the need to monitor the City and State during this critical phase.

rs in speaking about the need to monitor the City and State during this critical phase.

On the same day, a lengthy expose on Shingle Mountain by Washington Post national climate and environmental reporter Darryl Fears instantly made the dump a national poster child for Environmental Racism.

Two days later, Dallas Mayor Eric Johnson was asked about the Shingle Mountain clean-up by a Channel 8 reporter during his City Hall press conference on rising crime rates in Dallas. His revealing answer beginning with, “It’s really a legal problem,” confirmed the City always had the option of cleaning up the dump, but delayed doing so for over 18 months until it had received money from either the operators or landowners. Admitting that the City could have “solved” this problem early on, Johnson said the City choose not to because that would have made the City’s lawsuit against the landowners “moot.”

Moot is a lawyer’s term that’s defined as “of little or no practical value, meaning, or relevance; purely academic.” Instead of making their lawsuit moot by immediately cleaning up a site causing daily human health damage, Mayor Johnson and the City of Dallas rendered the health of Marsha Jackson and the Choate Street families moot. They made it of little or no practical value in the City’s approach. Of much greater value was the cash received by the landowners. The City sacrificed a street full of its own residents for a lousy $1 million.

In his three-m inute response, Johnson never uttered Marsha Jackson’s name, never addressed residents’ health issues, and never expressed regret, second thoughts, or apologies over the year and half the six-story waste pile harmed Choate Street residents. He never admitted the City’s multiple failures in code enforcement, zoning or environmental regulation that paved the way for Shingle Mountain’s creation. He complained how the City was put in a “tough position” – never considering how tough it might be for parents to watch helplessly as their child coughs-up pieces of ground-up shingles. Mayor’s Johnson’s answer was full of legal rationale but completely devoid of humanity or self-awareness. There were no people in it.

inute response, Johnson never uttered Marsha Jackson’s name, never addressed residents’ health issues, and never expressed regret, second thoughts, or apologies over the year and half the six-story waste pile harmed Choate Street residents. He never admitted the City’s multiple failures in code enforcement, zoning or environmental regulation that paved the way for Shingle Mountain’s creation. He complained how the City was put in a “tough position” – never considering how tough it might be for parents to watch helplessly as their child coughs-up pieces of ground-up shingles. Mayor’s Johnson’s answer was full of legal rationale but completely devoid of humanity or self-awareness. There were no people in it.

In short, it was an articulate if soulless synopsis of the City’s position regarding not only Shingle Mountain, but all environmental health problems in Dallas. Because at Dallas City Hall there is no such thing as human-centric environmental problems. What was the City’s first legal response to Shingle Mountain? It wasn’t to cite what an illegal awful abomination it was, but to take it to court over storm water violations. There were no people to worry about. Besides the inability of the City to protect its own residents from illegal hazards is the fact that it continues to treat Choate Street residents as spectators to their own disaster. Marsha Jackson is the Invisible Woman.

In May the Dallas City Council unanimously rejected the pleas of Ms. Jackson and Southern Sector Rising to re-establish the Dallas Environmental Health Commission to give an institutional voice to their concerns within City Hall; to put people back into the mix along with tree planting and water conservation. The Council turned its back on her – again.

That’s why your public comments about maintaining the safety of the pending clean-up are important.

Please show the City of Dallas that you care about Marsha Jackson and the families on Choate Street – even if it doesn’t. Thanks.

CLICK HERE TO SUBMIT YOUR COMMENTS

Help us Move Shingle Mountain

Choate Street families in Southern Dallas, including this child, and Ms. Marsha Jackson (pictured above) are still living under 100,000 plus tons of hazardous waste that was illegally dumped without their knowledge or consent.

It’s been almost three years since dumping began and two since the residents forced the dumping to stop, but the Mountain still remains, causing respiratory and neurological health problems for everyone on the street.

Shingle Mountain remains despite the City of Dallas having the legal authority and money to remove it. The City has had both for the entire three-year existence of the dump but has chosen to delay a clean-up in order to try to get the original operators to pay for it. That’s hasn’t happened.

On August 5th an alliance of over 30 groups, including Downwinders, sent a letter to the Dallas City Council and City Manager stating that if the City did not begin removing Shingle Mountain by October 1st, they would begin to do it themselves.

On August 29th, many of those same groups participated in the Shingle Mountain Accountability Convoy, a mobile four hour protest that saw the conviction of five elected officials for “reckless disregard for human life” in mock trials with the Shingle Mountain float as a centerpiece.

On August 29th, many of those same groups participated in the Shingle Mountain Accountability Convoy, a mobile four hour protest that saw the conviction of five elected officials for “reckless disregard for human life” in mock trials with the Shingle Mountain float as a centerpiece.

10 days later the City put out a bid request for the job of removing the waste from Shingle Mountain. That process is over on October 5th. Despite this positive development the Dallas City Manager stated THIS WEEK that it would still be 2-3 months before an actual clean-up began.

THAT IS UNACCEPTABLE.

Downwinders and other groups are asking you to help respond to this continued delay in TWO ways:

1) CLICK HERE to send an email message to the Dallas City Council that says “Move the Mountain Now!”

It’s already written and addressed at our website’s “Featured Citizen Action” – all you have to do is fill in your contact information and click and away it goes. You can add your own message if you like as well.You may not be able to do much else right now, but you can send an email on behalf of these families.

2) Attend the Shingle Mountain Non-Violent Civil Disobedience training session This SUNDAY 2-5 pm

For the first time in our 26-year history we’re endorsing civil disobedience and training people who want to put themselves at risk of arrest on behalf of the Shingle Mountain families and those that want to support them when they do.

Last Sunday was our first training session. It attracted 20 people. We’re hosting another training session THIS SUNDAY 2-5 pm in Dallas at the GoodWorks

Co-Working space where Downwinders is headquartered. Masks are required and social distancing will be enforced. Training will occur outside.

In 2019, the threat of civil disobedience by Choate Street residents and their supporters was the only thing that got the City of Dallas to change its mind and close down active operations at Shingle Mountain. After another year of trying to

clean-up this on-going disaster with meetings, we’re tired of the City’s willful neglect and cruel delay that’s harming human health. We need to again show we’re willing to go to the mat for this outrage.

You don’t have to be sure you want to risk arrest. You just have to want to help. Support roles for those getting arrested are critical. Whether you want to risk arrest or provide support you must have this training.

Just having more names on this list will send the City an important message. Please consider showing up and adding yours. Thanks.

D Magazine on Marsha Jackson’s Lawsuit

D with the first story about Marsha Jackson’s lawsuit….”the suit blames the city for (Shingle Mountain’s) existence. It says existing deed restrictions should have blocked the city from issuing a certificate of occupancy, but the operators got one anyway. The city didn’t require the operator to get a special use permit or even have a site plan, it alleges. More broadly, it says the city’s zoning purposely steers similar sites to Black and Latino neighborhoods and, despite having removed other large polluters away from nearby developments like Trinity Groves, has refused to do the same for Shingle Mountain.”

Citing Overt Racism, Marsha Jackson Sues Dallas over Shingle Mountain

of ground-up shingles next door to her house assaulting her health.

Arguing that the City Of Dallas has always had the authority to clean-up the huge illegal Shingle Mountain dump in Southern Dallas, but chose not to because it’s in a predominantly Black and Brown neighborhood, lawyers for Marsha Jackson added City Hall as a defendant in their federal lawsuit.

Dallas joins the Rogue’s Gallery of grifters, including former operator/con man Chris Ganter and his accomplice landowner Cabe Chadick, being sued by Jackson’s lawyers, famed civil rights attorneys Mike Daniel and Laura Beshara.

At issue is the creation and continuing health threat caused by Dallas’ largest illegal dump – a 100-foot high, 100,000 ton pile of asphalt shingles that began surrounding Jackson’s house in Janury of 2018.

Speaking on behalf of Jackson’s in their amended complaint filed July 8th Daniel and Besharal state, “The City, along with the operator and owner, is responsible for the existence of Shingle Mountain.” The trail of official negligence they document backs that claim.

Shingle Mountain’s operators were in violation of numerous city regulations and laws the day it opened. They violated a specific deed restriction put in place to prevent the very dumping from which they profited. They didn’t have a required Special Use Permit. They didn’t have any solid waste or storm run-off permits. They had no pollution permits to spew asphalt dust into the air by the tons. And they had set up shop in a floodplain which made the entire business an illegal use. Incredibly, the City of Dallas issued the dump a Certificate of Occupancy anyway.

But the suit does more than document the specific abuses leading up to the creation of the Shingle Mountain crisis. It also cites a pattern of racist zoning the City knowingly put in place that practically rolled out the red carpet for the con men responsible for the dump.

The City Council deliberately changed the zoning on the Shingle Mountain dump site to the heaviest industrial zoning possible despite knowing that Ms. Jackson’s home and other homes were adjacent to the site. The City changed the zoning knowing that the heavy industrial zoning adjacent to the homes violated City zoning policies.

Jackson’s suit points out there are no industrial dumps in predominantly White residential neighborhoods in Dallas. The City Council hasn’t approved or contributed to the presence of illegal dumps in predominantly White residential single-family neighborhoods. The City hasn’t issued permits in violation of deed restrictions and doesn’t impose heavy industrial zoning adjacent to single family homes in predominantly White residential neighborhoods. There are no Shingle Mountains or any illegal dumps in a predominantly White residential neighborhoods in Dallas. With only one limited exception there’s no industrial zoning adjacent to ANY predominantly White neighborhoods in Dallas.

It also cites several example of when the City moved quickly to pay for contaminated sites…when developers requested it. In 2010 the Dallas City Council expended over $1 million in City funds to provide for the removal of lead soil contamination for the construction of Belo Garden park downtown. In 2015, the Dallas City Council paid $2.5 million in City funds to relocate and remove the Argos batch plant out of the newly gentrified “Trinity Groves” district and relocate it deeper into West Dallas where it’s adjacent to Black and Hispanic neighborhoods.

But in 2019, when Marsha Jackson requested funding for the clean-up of Shingle Mountain because of escalating health problems, the Dallas City Council refused.

As a result , Jackson’s lawsuit against the City is for: 1) violation of the federal environmental laws by contributing to the creation of the illegal landfill and 2) for treating her differently on the basis of race by creating the industrial zoning that is harming her and by failing to remove the illegal landfill when the City acts to perform environmental remediation in white areas. Ms. Jackson’s suit against the City asks for the City to enter onto the Shingle Mountain property and remove the illegal landfill. She asks for the City to clean up the Shingle Mountain property to remove the environmental and health hazard and to re-zone the property to a compatible use for the homes that are next to the location.

Since the first day it opened for business without any warning, Ms. Jackson and her neighbors have complained about health problems, including respiratory and neurological problems. Specifically, they’ve cited poor air quality resulting from the black dust permeating the air they were breathing. Three years of decomposition is stripping carcinogens and toxins like Silica, Formaldehyde and fiberglass from their adhesive backings and putting them into the air as Particulate Matter pollution. In these summer months, standing downwind of the dump is like standing next to an asphalt batch plant or oil terminal, with fumes overwhelming even the most healthy.

Perhaps most infuriating of all is the argument by Jackson’s lawyers that the City has had the authority to act to remove the dump at any point over the last almost-three years:

“The City of Dallas has the legal power to require the removal of Shingle Mountain. It can summarily abate the use because it is located within the floodplain. The use is not one allowed by the City in a flood plain. Texas law gives the City of Dallas the power to abate the violation by causing the work necessary to do so after notice and an opportunity to comply to the owner. If the owner, as in this case fails to comply, the City, without legal action, may pay for and cause the work to be done and assess the costs to the owner. Until the costs are paid,interests at 10 percent per year and the City has a lien on the property for the costs incurred and the interest. (Tx. Local Gov’t Code. § 54.020.)”

After three years Dallas has seemingly run out of excuses for its discriminatory treatment of Marsha Jackson and her neighbors. A well-worn truism is that the only time the City responds to its residents is when a lawsuit is at stake. Now that the City has been named a “responsible party” to the crisis in a lawsuit, Jackson’s plight might actually be a priority at City Hall.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/dmn/KAAKWCLEMNCRXNYABMHB33CEPA.jpg)