Incineration

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals Linked to Endometriosis

Another example of the insidious nature of endocrine disrupting chemicals is out.

Another example of the insidious nature of endocrine disrupting chemicals is out.

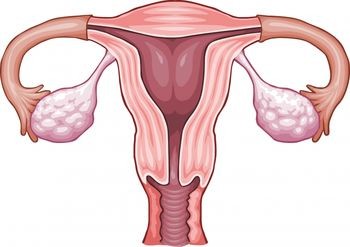

This week saw the publication of a study from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Maryland that shows an association between women with higher levels of a estrogen-mimicking pesticide and increased incidence of endometriosis.

Women were divided into groups with pelvic pain and no symptoms. Those with pain were more likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis if they had high blood levels of the estrogen-like pesticide hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH). Although HCH has been banned as a crop pesticide in the United States, it builds up and persists in the environment, so it remains in some food supplies.

Women with the highest blood of a sunscreen chemical, benzophenone, in their urine also had a higher risk of endometriosis according to the study, published in Environmental Science and Technology.

“Our studies are beginning to corroborate the idea that environmental estrogen may be associated with endometriosis,” said the Institute's Director Germaine Buck-Louis. But the link has a long toxicological history.

In 1993, the connection between endometriosis and environmental chemicals was discovered when Rhesus monkeys fed food contaminated with dioxins – hormone-disrupting pollutants created by waste incinerators and other industries – developed endometriosis 10 years later. (The Midlothian cement plants and the Exide lead smelter in Frisco have been the the largest industrial sources of airborne dioxin in North Texas over the last decade.)

A 2009 Italian study linked the disease, which stimulates uterine tissue growth in the ovaries or other parts of the body, to PCB and DDT exposure. Both are endocrine disrupters

“It’s certainly plausible that any outside source that alters estrogen levels, even slightly, could contribute to gynecological diseases,” said Dr. Megan Schwarzman, a family physician at San Francisco General Hospital and an environmental health scientist at the University of California, Berkeley who was not connected directly with the Institute study.

With 80,000 chemicals and counting in the marketplace to be exposed to, it's more than plausible.

Exposure to Phthalates (Plastics) Linked to Diabetes in Women

Just last week we mentioned that one of the chemicals to look out for in burning plastics was phthalates – a class of widely-used chemicals that make plastic more plastic, i.e. more flexible. Phthalates are used in perfumes, cosmetics, and lots of household items made with Polyvinyl Chloride. This is how the stuff ends up in garbage, and how it can end up in your lungs when that garbage is burned at a cement kiln or power plant as "fuel" in the name of "recycling."

Just last week we mentioned that one of the chemicals to look out for in burning plastics was phthalates – a class of widely-used chemicals that make plastic more plastic, i.e. more flexible. Phthalates are used in perfumes, cosmetics, and lots of household items made with Polyvinyl Chloride. This is how the stuff ends up in garbage, and how it can end up in your lungs when that garbage is burned at a cement kiln or power plant as "fuel" in the name of "recycling."

This isn't a theoretical problem. When Midlothian area residents began collecting their own air samples downwind of the local hazardous-waste burning cement plants in the 1990's, they often found significant levels of phthalates.

From past research we know that exposure to phthalates in the womb can disrupt male hormones and have a range of health effects including feminizing male genitalia and reduced IQ.

And guess what? Ellis County rates of Hypospadias (a congenital birth defect in which the opening of the urethra is on the underside, rather than at the end, of the penis. are almost twice as high as for the state a a whole.

This week comes the news that Harvard scientists have linked phthalates to diabetes among women, and particularly to women of color in the Latino and Black communities who experienced the most exposure. Among these populations the risk of diabetes was double. The researchers cautioned that they don't yet know if phthalates actually cause the disease, but they seemed sure of an association.

“It’s extremely likely that phthalates and other chemical contaminants will turn out to be a big part of the obesity and diabetes epidemic, but at this point we really don't know how these chemicals are interacting with each other, or with the human body.”

Diabetes, an endocrine disease marked by problems with insulin production or insulin resistance, affects nearly 26 million Americans, or 11 percent of the population older than 20, according to CDC data. People of color already suffer disproportionally from the disease. According to the Centers for Disease Control, blacks have a diabetes rate 77 percent higher than that of whites, while Latinos have a 66 percent higher rate.

The Harvard study is at least the third in in two years to link phthalates to diabetes in women or adults in general.

“With phthalates, the story is really still emerging,” said Kristina Thayer, a researcher with the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program. “Studies like these are considered exploratory, but they seem to be consistent.” “More needs to be done to really fill in this question of potential causality, and the roles that specific phthalates may play,” she added.

But don't expect the Chemical industry, EPA, or the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to be concerned about this lack of information on the health effects of phthalates exposure. Don't expect them to postpone decisions about burning garbage for fuel because of these gaps in knowledge. Allowing things to happen without fully accounting for all of their hazards is just another day at the office for them. If you want these things to happen, you're going to have to Do-It-Yourself.

The Next Big Dallas Environmental Fight? Garbage Burning

Many folks in the DFW environmental community think the battle over "flow control" at the McCommas Bluff landfill in Dallas is merely a prelude the the bigger goal of locating a large "materials recovery" operation there that will include a waste-to-energy power plant that can generate cash for City Hall as well as electricity. Once confined to the land-starved East Coast and Midwest, garbage burning is coming to Texas under the cover of recycling schemes that want to use it to make a buck instead of paying a landfill to take it.

Many folks in the DFW environmental community think the battle over "flow control" at the McCommas Bluff landfill in Dallas is merely a prelude the the bigger goal of locating a large "materials recovery" operation there that will include a waste-to-energy power plant that can generate cash for City Hall as well as electricity. Once confined to the land-starved East Coast and Midwest, garbage burning is coming to Texas under the cover of recycling schemes that want to use it to make a buck instead of paying a landfill to take it.

A wave of garbage-burning permits have been approved across the country over the last 2-3 years at various cement plants, including the TXI kiln in Midlothian, south of Dallas, which can now burn plastic wastes and the non-steel parts of cars, including brake linings, electronic switches, vinyl covers, mats, and dashboards. Now the groundwork is being put in place to extend that practice into municipal garbage burning using power plants.

The sale pitch sounds great. The waste companies and city will be "completely committed" to recycling and reusing as much waste as possible. They'll only burn a "small percentage of leftover waste" that would otherwise go to a landfill. It has "significant BTU value" and it "reduces pollution" when you burn it! Why bury it when you can use it to make power that people need. It's really just like recycling!

Except it isn't. It's garbage burning. It's burning plastics. It's burning "fibers." It's burning teated lumber. It's burning "a small list of alternative fuels" and when there's not a enough of that stuff to generate the required power, the list expands. And it produces more air pollution, and distributes that air pollution over a much larger area, affecting many more people, than the same amount of garbage continuing to go to a landfill.

The 20-year fight over burning hazardous wastes at TXI and the other Midlothian cement plants began with the companies telling residents that they were "recycling flammable liquids" in kilns that reached almost 2000 degrees, and burned up 99.99% of all the waste. Soon, the cement kilns were mixing in non-flammable solids like toxic metals, and wastes with chlorine, and contaminated water that had little or no BTU value at all. And far from removing 99.99% of the bad stuff, the kilns added a toxic soup of chemicals to their already voluminous amounts of air pollution.

A landfill's toxic plume is usually slow-moving, flows only downhill, and can be tracked as it goes through soil. An incinerator's plume is blowing toxic air pollution wherever the wind is blowing, traveling as far the the wind will carry it, and changes from day to day, often eluding monitors if they're not in exactly the right place. Then, after all that, there's the problem of what to do with all the toxic ash. Send it to a landfill. Which practice puts more people in harm's way? Which one affects public health more? Which is the more sustainable alternative?

A landfill's toxic plume is usually slow-moving, flows only downhill, and can be tracked as it goes through soil. An incinerator's plume is blowing toxic air pollution wherever the wind is blowing, traveling as far the the wind will carry it, and changes from day to day, often eluding monitors if they're not in exactly the right place. Then, after all that, there's the problem of what to do with all the toxic ash. Send it to a landfill. Which practice puts more people in harm's way? Which one affects public health more? Which is the more sustainable alternative?

As a means of getting tuned up for the fight ahead, which some rumors put as near as this fall or winter, let's examine a little study partially sponsored by the American Chemical Council that was published the other day with the intent of setting the stage for widespread garbage, sorry, "refuse" burning.

It comes from UT – where another study on energy just got a lot of unfavorable publicity. This time It's Dr. Michael Webber who's Associate Director of the Center for International Energy and Environmental Policy in the Jackson School of Geosciences, Co-Director of the Clean Energy Incubator at the Austin Technology Incubator, Fellow of the Strauss Center for International Security and Law at the LBJ School of Public Affairs, and Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Texas at Austin. Whew.

He's also a member of the "Pecan Street Project" in Austin, which is a "citywide, multi-institutional effort in Austin to create the electricity and water utilities of the future by the innovation and implementation of smart grids, smart meters, and smart appliances. The Pecan Street Project team includes UT, the City of Austin, Austin Energy, the Environmental Defense Fund, the Austin Technology Incubator, and eleven corporate partners."

See? Already the guy has impeccable credentials.

And what is Dr. Webber and the American Chemical council selling today?

"If 5% of residual waste from recycling facilities were diverted to energy recovery, it would generate enough power for around 700,000 American homes annually."

First, you understand that Dallas alone has more than 700,000 homes, and so we're talking about burning 5% of the entire nation's leftovers to get electrical energy for a city smaller than Dallas…for a year.

Second, does anyone know how many waste incinerators would have to be built and and what cost, or how they'd be financed? Nope. But we digress….

"The study found that while single-stream recycling has helped divert millions of tons of waste from landfills in the U.S. – where recycling rates for municipal solid waste are currently over 30% – Material Recycling Facilities (MRFs) currently landfill between 5% and 15% of total processed of the material treated as residue.

According to the researchers this residue is primarily composed of high energy content non-recycled plastics and fibre.

The report proposed that one possible end-of-life solution for these energy dense materials is to process the residue into Solid Recovered Fuel (SRF) that can be used as an alternative energy source capable of replacing or supplementing fuel sources such as coal, natural gas, petroleum coke, or biomass in many industrial and power production processes."

You will be unsurprised to learn that a cement kiln was involved in "testing" how well the

You will be unsurprised to learn that a cement kiln was involved in "testing" how well the garbage, sorry, SRF burned. Because it can reach temperatures of almost 2000 degrees!

But the results are not exactly spectacular in the way the Chemical Council probably anticipated.

Sulfur Dioxide (Sox) pollution was reportedly reduced over what coal alone would have emitted by some 20 to 44% (the study rounds this number up to "roughly 50%"). OK. but that's what SOx "scrubbers" are for. The study doesn't say whether the kiln used for the experiment had scrubbers on it. Not a lot of them do right now, but most power plants do and any new power plant or cement kiln would have to have them as well. Both the TXI and Holcim dry kilns have scrubbers already, and the new Ash Grove dry kiln will as well. These scrubbers can reduce SOx pollution by over 80%. So can we agree that we're better off just adding scrubbers to facilities instead of setting fire to plastic garbage to reduce this kind of air pollution?

On the other hand Nitrogen Oxide (NOx) pollution reportedly went up 25% to as much as 93%, when garbage was burned compared to coal. This spike was explained away by saying the kiln didn't have a proper delivery system for the garbage to reach the kiln. That's untested speculation by the authors that may or may not be true. Any increase in smog-forming NOx pollution would be hard to sell in an area like DFW that's been in violation of federal smog standards for over 20 years.

CO2 emissions were reportedly reduced by a paltry 1.5% – the equivalent to getting a million cars off the road! But that's another small number when you realize that just treating the CO2 from the three Midlothian cement plants here in North Texas would get you that number or something even bigger.

When you burn plastic you get dioxins – one of the most toxic substances in the world. The Chemical Council knows this. But there was no testing for dioxins, or phthalates, or any of the more exotic kinds of air pollution one would expect to see when you burn plastics and other kinds of garbage. This is one of the primary objections citizens would have about this practice, and yet there was no testing for it.

These results may not seem that great to you, but they impressed both the Chemical Council and Dr. Webber.

"In this case, one person's trash truly is another person's treasure. Americans send tons of waste to landfills each and every day, meaning that one of America's most abundant and affordable sources of energy ends up buried in landfills," commented Cal Dooley, president and CEO of ACC.

"It's time we got smart and made energy recovery a central part of America's energy strategy," he added.

Meanwhile Dr. Webber added: "The findings from our study demonstrate how engineered fuels can make a meaningful contribution to our nation's strategy while reducing carbon and sulfur emissions compared to some forms of energy,"

Let's translate: "Your trash is our potential treasure. We can't portray ourselves as "Green" if we don't find some way to make plastics more eco-friendly. Plus, we can make a buck packaging our garbage for you to burn it. Our findings show that under these very controlled circumstances, and with not too many questions asked, burning garbage can make some minimal pollution reductions that other readily available alternatives could make better, while also increasing the kind of pollution that most people don't want."

This fight over garbage burning will be as big, if not bigger than the fight over gas drilling. It will involve environmental justice issues, toxic pollution, private-public contracts, sustainability, and real recycling vs the fake kind. And lots and lots of doublespeak. Get your waders on.

Mesopotamia or Midlothian – Burning is Bad

Here's a great story from Wired that reports the results of the first tests done in and around the places where the military's "burn pits" were located during the most recent Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Here's a great story from Wired that reports the results of the first tests done in and around the places where the military's "burn pits" were located during the most recent Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Not familiar with "burn pits?" If you grew up in rural Texas you are because it's exactly the way your grandfather got rid of his family's trash – by putting it in a big pile and then putting a match to it. Besides turning a ravine into an impromptu landfill, burn pits are the most popular way of disposing of your garbage when Waste Management just can't get to you.

In the military, burn pits were the disposal option of choice for everything: human waste, paints and paint removers, asbestos insulation, plastic and styrofoam containers, old computers and monitors – any waste you can imagine being generated at a front line military base.

Not surprisingly, troops that spent time around these open-air waste incinerators have been complaining about chronic bronchitis, neurological disorders, and rare cancers – just like people who live dowwnind of waste burning at cement kilns and incinerators. Military spokespersons have reassured these whiners that there was "no specific evidence" of the pits doing any human health damage. To which all of you who've been doing this for a while will respond: "How many times did anyone look for such damage?" The answer is zero – until now. Pulmonologist Dr. Anthony Szema of the Stony Brook School of Medicine, just released the results of an experiment that links the burn pit dust to immune system damage. Dr. Szema exposed 15 mice to the dust from the remains of a burn pit in Iraq. When collected on-site, the pit still stunk with the incinerated remains of animal carcasses, lithium batteries, printers and glues. This lovely cocktail of toxins was then inhaled by the mice and researchers tracked their respiratory system and spleen for signs of strain. And they got them.

Lung inflammation occurred within two hours of exposure, and T-cells dropped by a third. T-Cells are a critical component of the human immune health originating in the bone marrow but then going to the Thymus to finish their development. AIDS and other immune destroying diseases kill T-Cells. After two weeks of being regularly exposed to the burn pit dust, the mice had lost 70% of the T-cells they started with. "I can't even imagine what this date shows when you think about someone coming back from Iraq," Szema says. "these guys weren't inhaling the air once. They were working in it, sleeping in it, exercising in it. For days on end." Despite being limited to mice, Szema is confident that the results are transferable to humans. The symptoms of his mice line up with those being reported by veterans to a database at BurnPits360, a website dedicated to tracking the health of exposed servicemen and women. It's also one more step in understanding why different people react to pollution differently. With your immune system offline everyone is vulnerable to different inherent health weaknesses that are exacerbated. Dr. Szema isn't surprised at the results of his groundbreaking tests. "Based on the patients I've seen, this is a no-brainer. If anyone tries to say, ' Oh dust is just dust,' I can tell them that's simply not true."