An Underdog’s Thanksgiving

SMU’s conglomeration of millionaire students and multimillion-dollar buildings On The Hilltop might seem an unlikely place for a Thanksgiving tribute to people who steadily worked to undermine some of the more fantastic ambitions of the school’s alumni, and perhaps an even unlikelier place to find solace in their resistance.

But if you’re a DFW resident who’s curious about how the Status Quo can be un-Quoed, you might want to stop by the art gallery inside the SMU Student Union Building to see some ancient artifacts that show how things have changed, or not, since the early 1970’s. And while you’re there you might also want to give thanks to your predecessors, who were no less anguished, isolated, and outspent than you are now.

Entitled “Wide Open,” the gallery’s exhibit itself is meant to connect contemporary artists around the idea of Dallas as a “port city.” It includes everything from landscape-altering prophecies about the worst case climate change scenarios to the injury committed by even the smallest incidental industrial releases we might otherwise never notice. That’s the art. But there’s also the history.

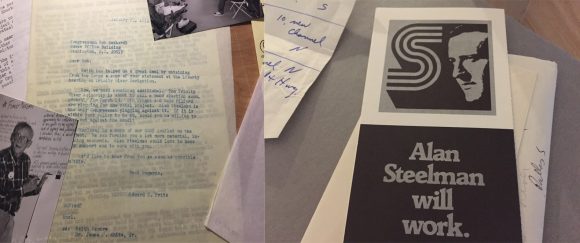

In the middle of the gallery there’s a single big floating table with a host of documents and memorabilia. Collectively they tell the creation story of the modern Dallas-Fort Worth environmental movement. And so much more. They tell you how to make Change happen, how to undo “done deals” and how “small groups of misguided people” bring down the ambitions of local power brokers.

In 1972, the economic engine which the Chambers of Commerce and elected officials agreed could zoom DFW past other growing Sunbelt rivals was …a barge canal from North Texas all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. It was going to be a Lone Star Panama Canal making us a prairie port city.

The canalization of the Trinity River was touted as a state-of-the-art engineering project that would make the region a commercial crossroads. The river already functioned as an open sewer for industries from the Northside slaughterhouses in Fort Worth to the lead smelters in West and South Dallas. The Trinity was smelled more than seen. Cementing its sides and straightening its bends looked like just a formality to the Powers-That-Be.

Supporting canalization were Dallas Congressmen Earle Cabell, (Dem), Jim Collins, (Rep) Fort Worth Congressman Jim Wright (Dem), Mid Cities Congressman Dale Milford (Dem), Dallas Mayor Wes Wise, Fort Worth Mayor Sharkey Stovall, and virtually all of the Fort Worth and Dallas downtown business establishment, led by the powerful Citizens Charter Association. You may know this group by its newer name: the Dallas Citizens Council.

Opposing them was birdwatcher and attorney Ned Fritz, and a small circle of citizens. And it’s his official archives at SMU’s Degolyer Library that were raided to populate the gallery table’s displays.

Fritz was Dallas’ original unrepentant treehugger. By the time Trinity River canalization came to a head, he’d already single-handedly stopped the channelization of Bachman Creek, which cut through his property, and successfully defended the wildflowers he grew in his front yard against the City’s attempts to force him to plant St. Augustine like everyone else. He also had a great deal of familiarity with the Trinity River as it ran through southeast Texas’ Big Thicket forest and as early as the mid-1960’s had begun advocating federal protection for this piece of exotic wilderness. He rightly saw the canal as the biggest threat to that goal.

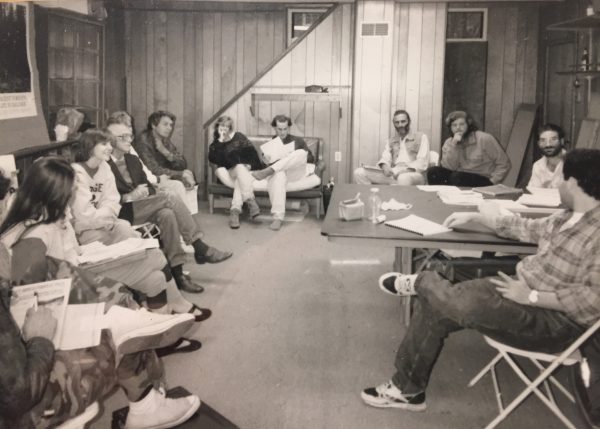

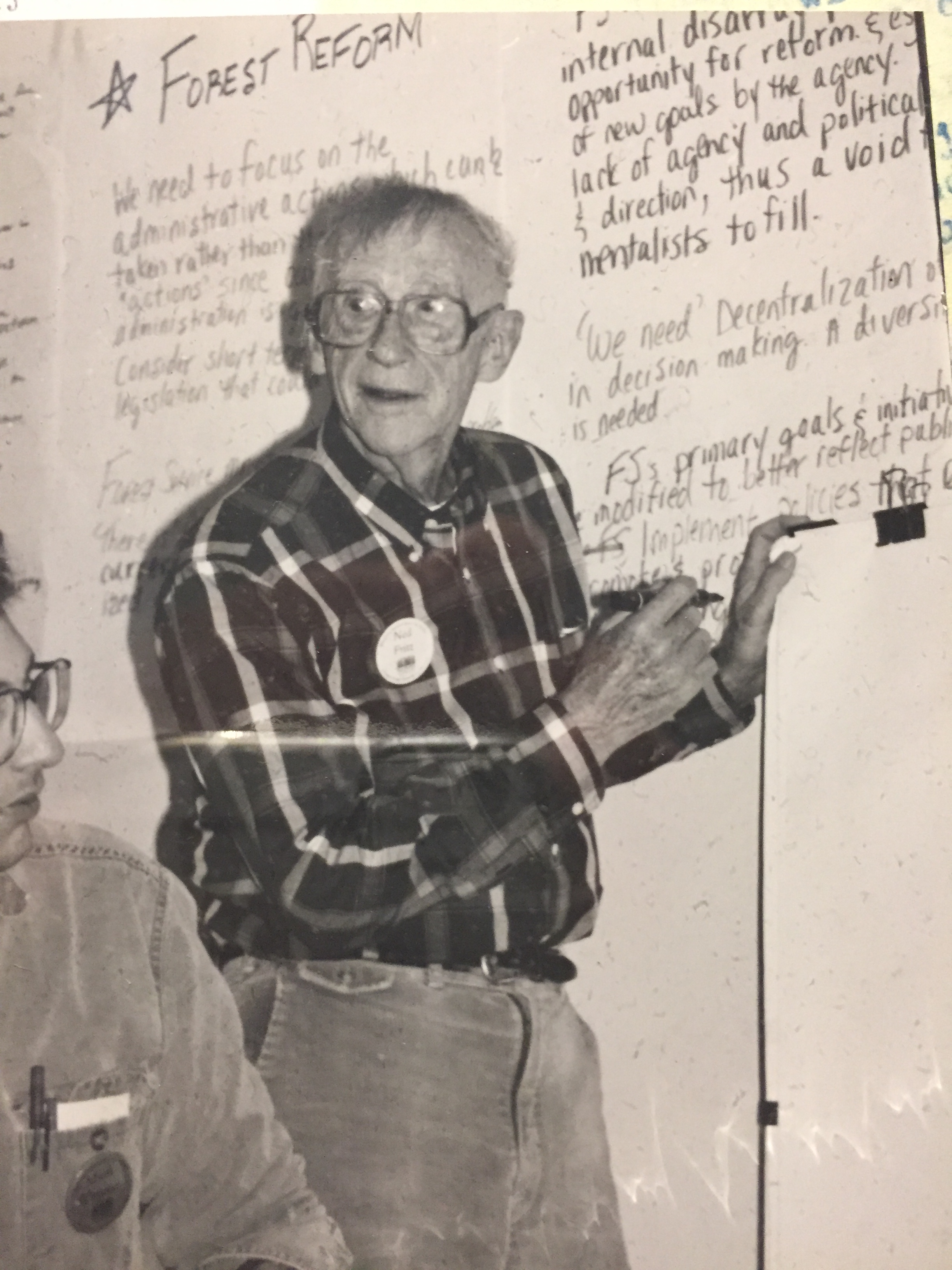

A COST meeting in the basement of Don Smith’s house.

On April 13, 1972, Fritz and a handful of other early canal opponents met at the house of SMU economics professor Don Smith and formed an organization called Citizens Organization for a Sound Trinity (COST). Among them was Henry Fulcher, a Republican businessman and James F. White, a theology professor at SMU, who both thought the canal, now estimated at $1.6 billion and growing, was an extravagant boondoggle. Jim Bush was a Navarro College student who’d grown up camping along the banks of the Trinity and Mary Wright was one of the leading Sierra Club members in Dallas. They both knew canalization would destroy the natural habitat and eco-systems of countless species.

Wright had met Alan Steelman at a Republican Women’s Club gathering in Dallas. A young and hipper Republican, Steelman was seeking the Republican nomination in May to run against much more conservative incumbent Democratic Congressman and avid Canal supporter, Earle Cabell in November (yes, that Earle Cabell).

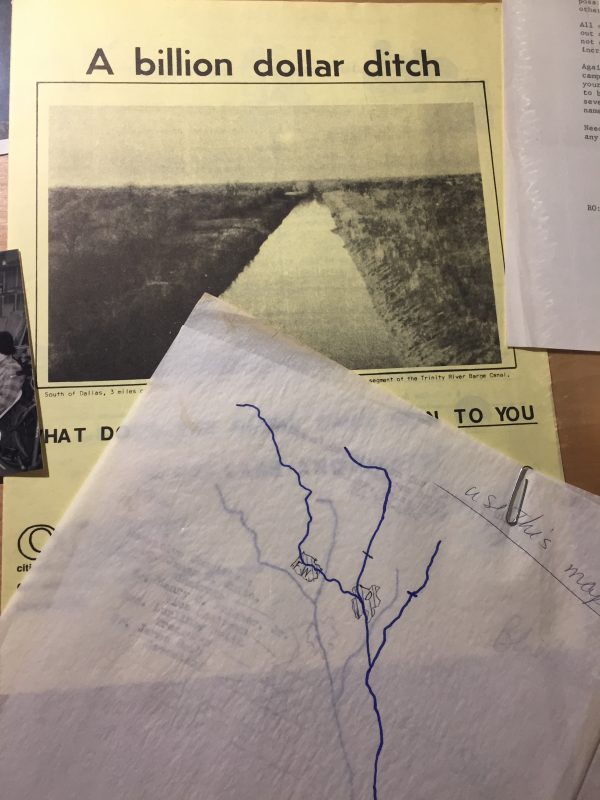

Wright briefed Steelman about the canal. Steelman listened. During the Republican Primary he wondered aloud whether Dallas needed barge transportation when the massive new regional airport between Dallas and Fort Worth was to begin operation in 1973. Steelman dubbed the project a “billion-dollar ditch.” He won the Republican nomination and headed to a showdown with Cabell.

On the left is a plea to Houston area Democratic Congressman Bob Eckhardt from Ned Fritz to come out against the Trinity River Canal to balance support in the DFW delegation – with the notable exception of Alan Steelman. On the right, a piece of Steelman Campaign literature.

Still, it was assumed the canal was a done deal. There were already federal appropriations for it. All the decision-makers were for it.

But in October 1972, at a small hearing of homeowners fighting an Army Corps of Engineers-planned channelization of Garland’s Duck Creek, a local bureaucrat let it slip that there would have to be a local bond issue to provide starter money for the canal. Uncle Sam was requiring the 17 counties along the Trinity River to put up $150 million in seed money.

This was the game changer. It was the first time that citizens in Dallas knew that the project was going to require some money from their pockets.

Then Steelman actually won his race against Cabell in November 1972 with an unexpectedly high 56 per cent of the vote.

This made the Local Establishment very nervous. The Charter Association and Chamber reflexively adopted the paternalistic downtown Dallas approach of not asking too many questions, citing a need to keep up with other cities, and claiming “only extremists would oppose this” great Big Idea.

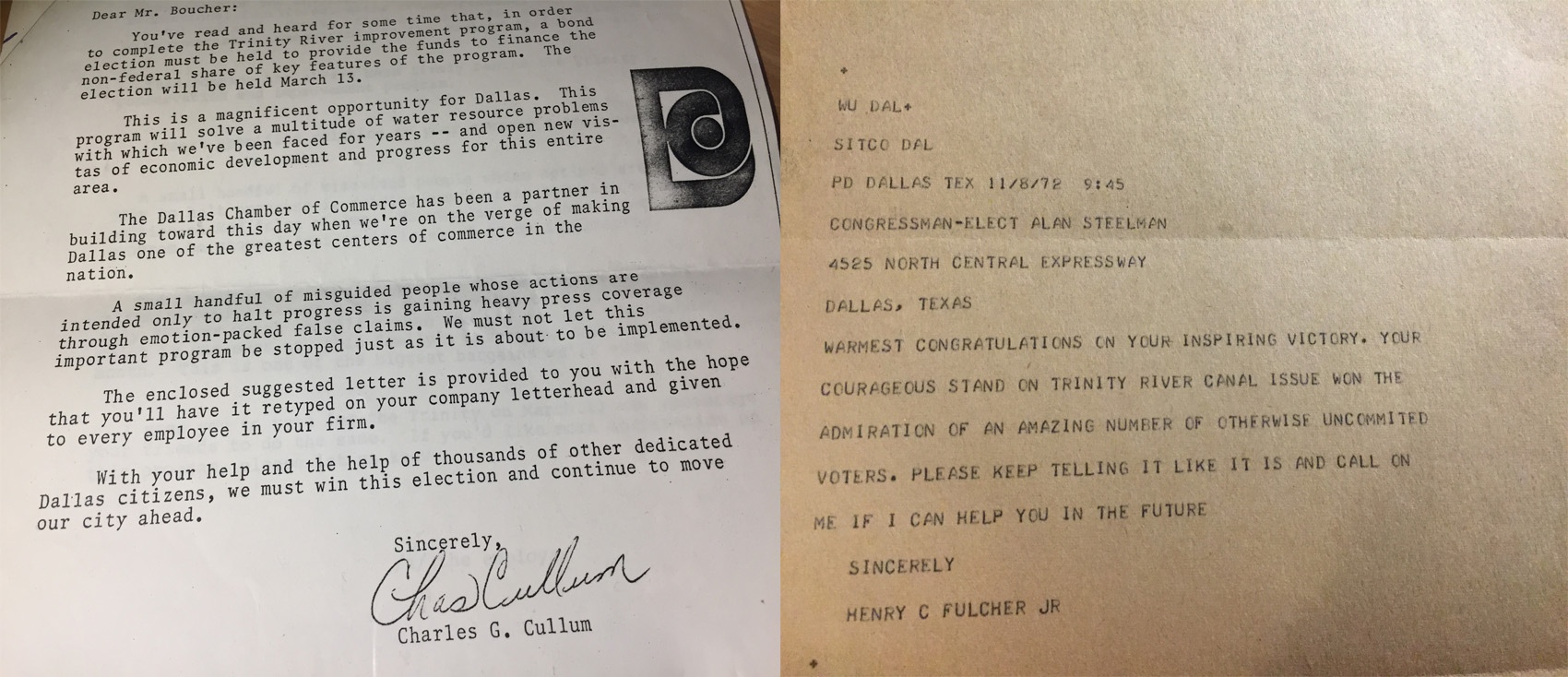

On the left is a letter from Tom Thumb founder and Dallas civic leader Charles Cullum, on behalf of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce, deriding Trinity River canal opponents as a “small group of misguided people”. On the right is a telegram to newly elected Dallas Congressman Alan Steelman from COST president Henry Fulcher congratulating Steelman on his victory over Canal advocate and incumbent congressman Earl Cabell in the Nov 1972 elections.

According to COST veterans, the Chamber’s name-calling “won more active opponents to the canal project every time they uttered it.” Anti-Establishmentarianism was getting local.

Congressional hearings that were considered a technicality before Steelman’s election now became a forum for growing discontent. Ned Fritz had a bigger, more receptive audience for his warnings and he had more allies. New studies confirmed downstream dams would wreak havoc on local species and ecosystems, and flood thousands of acres of hardwood forest. The Environmental Policy Center in Washington called the Trinity River canal project the nation’s “number one boondoggle.” A representative of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department said the project would cause “wholesale devastation” to the environment.

Canal backers panicked and set the bond vote before they thought opposition could catch fire. Passing up an opportunity to hold it in conjunction with city council elections in Dallas and Fort Worth and several other cities, or when the Dallas school board elections and several smaller city elections would be held, the Powers-That-Be set the vote for a totally different Tuesday in the middle of March. Officials said the election was purposely held separately from any other elections because the Authority felt the people “should not have the issue clouded with any other electoral matters.”

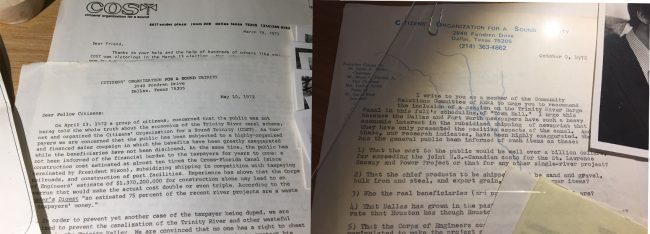

On the left is one of the first notices that opponents to Canalization had formed a group – COST. On the right is a request for local PBS station KERA to host a Town Hall on the Canal issue.

The date conveniently fell two weeks before an environmental impact study on the Trinity project was due to be released by the Corps of Engineers, and a few months before a revised Corps cost study was to be released.

Canal backers assembled an advertising and promotional campaign that would be familiar to anyone who just sat through two decades of Trinity Toll Road salesmanship. Estimated cost? $500,000 – $3 million in 2017 dollars.

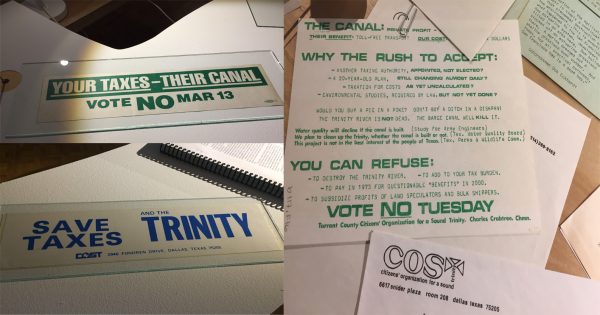

COST sprung into action too – with inexpensive radio ads and mailings. Opponents in Dallas and Forth Worth ended up spending a grand total of $22,000. A favorite COST slogan was “Your money, Their canal.”

Opponents figured that if they could get 56 % of the vote in Dallas County and break even in Tarrant County they could afford to lose by big margins in the other 15 down-river counties that had to vote on the project. A majority of all voters and a majority of the 17 counties had to approve the project for it to pass.

The vote turnout was overwhelming—almost twice as large in Dallas as three weeks later for the city council elections. Dallas voted 56 per cent against it, Tarrant County went 54 per cent against it; and opponents got 47 per cent of the vote in the other 15 counties, actually carrying seven of them.

Had Fritz and COST lost that fight, DFW might still be dealing with a host of environmental and social nightmares.

Imagine a second Houston Ship Channel stretching from Hutchins or South Dallas to Fort Worth, lining a concrete ditch with heavy industry on both sides, and anyone who accidentally falls in must be sent to the Emergency Room for a precautionary exam just for coming in contact with the water. Imagine the additional air pollution and risk of exposure to exotic carcinogens for Black and Brown DFW when all kinds of new undesirable industry moves to join the smelters and slaughterhouses in their communities – still doing gangbuster business in the early 70’s. Imagine the Great Trinity Forest as a container port. Imagine no Big Thicket. Imagine the river with no trees, no greenery of any kind, devoid of any natural relationship with the land it runs through. A billion-dollar ditch.

All of that was at stake. A completely different reality. And with only campaign couch money to spend, a small group of committed citizens created a much different future for us in the here and now almost 50 years later. Give Thanks.

And then realize that victory was anything but preordained. It was hard work. It was persistence. It was failure after failure until something stuck to the wall or a lucky break occurred. Letters, telegrams (telegrams!), and fliers on the gallery table offer a recognizable peek into COST’s strategy and tactics for anyone who’s ever taken on City Hall. You see the wheels of a campaign trying to turn and get traction.

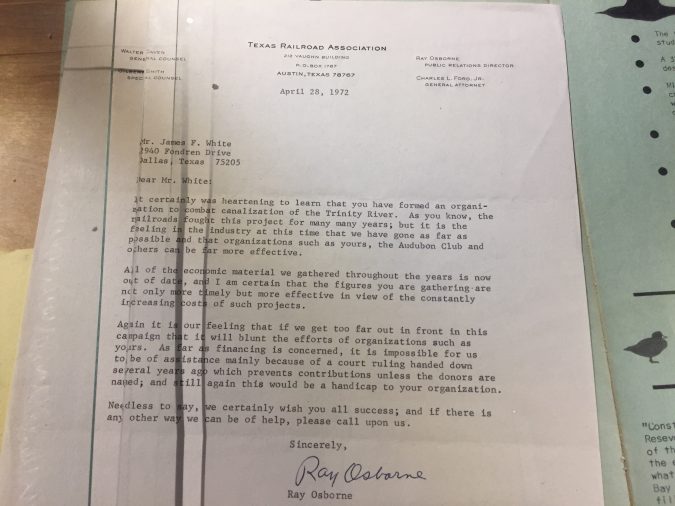

Who’s profitable ox would be gored with a canal? Railroads. On the gallery table is a letter from the rail industry agreeing with Fritz that the canal is a bad idea but begging off on coming out in full throat opposition and giving needed money to the cause. A good idea but a dead end. Since all the local DFW Congressmen were for the canal, would Congressman Bob Eckhardt from Houston come out in opposition? He did. Can we get Channel 13 to sponsor a televised Town Hall meeting on the Canal? Yes.

Opposing the canalization of the Trinity River was the work of “environmental extremists” even when you had SMU Seminary faculty, fiscally-conservative Republicans, and George Wallace supporters opposing the same thing. It was having the establishment do every. little. petty. thing. to insure your failure. It was not being certain if you were doing the right thing at the right time or not. It was having no real institutional support or guidance from anywhere, or anyone. It was Do-It-Yourself change-making from scratch.

In other words, it was very similar to now.

You can’t read the material about the Trinity River Canal at the gallery without seeing The Trinity River Toll Road as a sequel to the story it tells. It’s too easy to substitute Angela Hunt and other battle-tested toll road opponents for Ned Fritz and the canal when reading the business establishment’s knee jerk responses, or scanning the line-ups of the two sides. The names have changed, but the players are still the same. And the battle explored here not only follows the familiar contours of that road fight but any Dallas grassroots vs Establishment fight over the past decades – The Gas Wars, Fair Park, The Lead Smelters, New Freeways in Oak Cliff and South Dallas, etc.

Hunt, and other reliable opponents of newer Dallas Citizen Council Big Ideas like Scott Griggs and Philip Kingston have also been outspent, mocked, and isolated. And they’ve also won. Give Thanks.

Ned Fritz went on to found The League of Conservation Voters and establish what we now revere as The Big Thicket National Forest along with countless other accomplishments before he passed in 2008. He himself is a much-admired and oft-cited reference for many who would have found themselves on the opposite side of an argument with him when he was alive. Being dead tends to make you less threatening to the Status Quo.

Meanwhile the living spiritual descendants of Ned Fritz still remain at large and dangerous in the DFW area. Give Thanks…

…And get thee to SMU’s Temporary Temple of the Underdog before it closes on December 3rd.