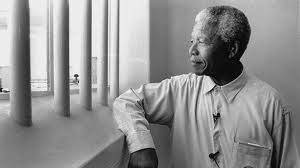

Small Stuff Adds Up: Nelson Mandela Edition

Today is "Nelson Mandela Day" across the planet in honor of one of the most persistent and righteous liberators in modern history. From our vantage point here in the 21st Century, his legacy is secure, the stuff of legends. He is the Father of the new South Africa, a symbol of freedom worldwide.

Today is "Nelson Mandela Day" across the planet in honor of one of the most persistent and righteous liberators in modern history. From our vantage point here in the 21st Century, his legacy is secure, the stuff of legends. He is the Father of the new South Africa, a symbol of freedom worldwide.

On the eve of Thanksgiving in 1984, a small group of Washington activists walked into the South African Embassy on Massachusetts Avenue. They had grown weary of their frustration with the intractable racial injustice in South Africa. They saw a system they did not like. They wanted to do something about it. It was the kind of bubbling disturbance that, if timed right, can launch a movement.

U.S. activists had tried before and failed to bring attention to the situation an ocean away, where 23 million black South Africans were ruled by 4.5 million whites, forced to carry passbooks, and killed, beaten or thrown in jail for bucking apartheid. Mandela, then a leader of the freedom movement, had been in prison for 20 years. He was not a household name in America.

With a little planning and the hope that they could get some attention on a slow news day, Robinson and other Washingtonians — including Mary Frances Berry, Eleanor Holmes Norton, and Walter E. Fauntroy — began a protest at the embassy. They told the South African ambassador of their demands: freedom for Mandela and the release of political prisoners.

That first day only a handful were arrested in front of the embassy. Besides raising awareness about Mandela's fate, the protesters were also trying to spotlight the Reagan administration's policy of "constructive engagement" with the all white, pro-apartheid South African government. They succeeded. Their arrests made international news that day and began a movement. Not only did the arrests in front of the South African embassy continue, occurring almost every week for years, but they also spawned a campus-based "divestiture" movement that demanded colleges and universities purge their stock portfolios of all companies still doing business with the all-white South African dictatorship.

With new Congressional allies, the movement passed the 1986 Anti-Apartheid Act, putting the first American sanctions on South Africa into place. One of the most segregated places on the planet had officially lost the support of its largest and most important sponsor. By 1990, over 160 companies had quit doing business in South Africa and over 4000 people had been arrested in front of its Washington embassy. South African leadership was totally isolated and losing economic steam fast. Nelson Mandela was released from prison that same year, going on to become the first democratically-elected president in its history.

“When we remember Mandela’s life, and we remind ourselves of his commitment and his bravery, it is easy to see the path to success,” Robinson said. “What requires great imagination, and great courage, is to see it from the other side.” In the mid-1980s, it seemed systematic, intractable and unyielding.

In a couple of months, the South African embassy in Washington DC will unveil a nine-foot tall bronze statue of Mandela giving the raised fist salute as he emerged from his Robben Island jail cell. It will be placed on the very spot those first protesters stood almost 30 years ago.

The Free South Africa Movement is a template for how small acts of resistance can grow into something powerful and history-changing. It doesn't always happen, but it can. Timing, strategy, and a little bit of luck all have to combine, but it can happen, if like Mandela himself, and then his supporters, you are extremely persistent, and use your head.

You think about these things very strategically. What can move the needle and what will likely not,” said Randall Robinson, the founder of TransAfrica, the oldest African American foreign policy organization in the United States. “You can protest. But if you can make the wind move, you have to put a sail up. To make the wind move where there is no sail is useless.”

Even though it was decades ago now, this lesson still resonates for everyone who's trying to express a visceral outrage over a perceived injustice, whether it's the Trayvon Martin verdict, or the Keystone Pipeline.

Small stuff adds up.