Posts Tagged ‘Air quality Monitoring’

Transformational National Science Foundation Grant for 21st-Century Air Monitoring Gets a Call Back

In a milestone for the local consortium Downwinders At Risk is working with to bring DFW air quality monitoring into the high-tech era, its $3 million request to the National Science Foundation for funding two pilot projects got a call-back last week.

In a milestone for the local consortium Downwinders At Risk is working with to bring DFW air quality monitoring into the high-tech era, its $3 million request to the National Science Foundation for funding two pilot projects got a call-back last week.

Led by University of Texas at Dallas high tech guru Dr. David Lary, the group includes scientists and researchers from the University of North Texas and UNT’s Health Science Center, Texas Christian University, the cities of Dallas, Fort Worth Plano and Richardson, the Fort Worth Independent School System, the Dallas County Community College District, the Fort Worth League of Neighborhoods, Livable Arlington, Mansfield Gas Well Awareness, and Downwinders at Risk.

There were said to be over 200 applicants applying for the NSF’s “Smart and Connected Cities” grant when the deadline passed about a month and a half ago. The NSF isn’t revealing how many of them got a follow-up “Virtual Site Tour” of the proposal, but the number isn’t believed to be very large. Rumor has it that one of the main competitors to the DFW proposal is Argonne National Laboratories, a 70-year old gigantic research industrial complex born out the Manhattan Project.

That a group that wasn’t even in business a year ago is now in the running with such a Colossus in a very competitive nationwide talent contest for valuable and scarce research dollars is pretty remarkable on its own. What makes it even more remarkable is that staff at the NSF itself actively discouraged the DFW project from even applying, because they didn’t think the proposal could compete with the scientific heavies already in the race.

That a group that wasn’t even in business a year ago is now in the running with such a Colossus in a very competitive nationwide talent contest for valuable and scarce research dollars is pretty remarkable on its own. What makes it even more remarkable is that staff at the NSF itself actively discouraged the DFW project from even applying, because they didn’t think the proposal could compete with the scientific heavies already in the race.

But what the NSF staff underestimated was how much the DFW project challenges and changes the status quo from the bottom up. It’s hard to imagine a proposal that has the potential to deliver more benefits to more people.

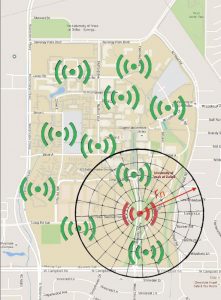

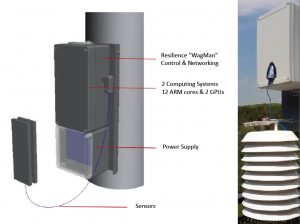

At the heart of the vision for the DFW grant proposal is the idea of an independent network of hundreds, then thousand of small e-sensors placed in a thought-out grid across the entire urban core of the Metromess. These sensors would be located every kilometer or even half-kilometer, block by block, down major thoroughfares, by schools and parks and daycare centers, by facilities that pollute.

So instead of relying on a handful of clunky large official EPA/TCEQ monitors scattered over an area the size of a couple of New England states, you know have data from just outside your own door.

Moreover these sensors would be able to deliver information about air quality in real time to an app on your phone or computer. Contrast this with the two-and-a-half hour wait between sampling and result you see on the official monitor websites now.

But wait, there’s more. As part of the app, you’re made aware of local conditions via an avatar or virtual human, who you can design yourself from a number of attributes. It will present you a list of health symptoms the poor air quality might trigger. But this avatar is also interactive through the network “portal.” You can upload your own symptoms when you’re having a bad air day. The software will look for correlations – wind direction and speed, concentrations of pollutants and allergens in the air, etc. and alert you when days are shaping up to be like the ones that give you trouble.

In the same way many of us now check the weather forecasts, pollen counts, and ozone alerts to know if we need to take extra care with our lungs, you can use this network and software to fine tune that investigation to a degree never before possible.

Want to be a neighborhood air pollution watch cop? Use the software to track down hotspots you didn’t even know existed, or enforce the permits issued to local facilities. The network of sensors allows you to track plumes in real time as they cross county and city boundaries.

Want to be a neighborhood air pollution watch cop? Use the software to track down hotspots you didn’t even know existed, or enforce the permits issued to local facilities. The network of sensors allows you to track plumes in real time as they cross county and city boundaries.

This is all administered by an independent group of researchers, colleges, scientists, municipalities, and public health specialists, not the State of Texas or EPA. And it’s all made possible by the same leaps in technology behind smart phones, smart cars, and even smart refrigerators: the ability to cram larger and larger tech capacities into smaller microchips and sell them for less money.

While the aim is to grow a huge network of sensors, the submitted NSF grant proposal calls for establishing two separate smaller pilot project grids of 40 sensors a piece – one grid in Southeast Fort Worth and one in Central Plano.

As the proposal explained, the differences in these two communities represent different ways to use the sensor network.

SE Fort Worth is a predominantly African-American and Latino neighborhood with documented high childhood asthma rates, high absentee rates in its schools, and for much of the year lies downwind from the Midlothian cement plants.

There the network can demonstrate how it can become a household health consulting tool, as well as empower neighborhood groups to address micro and macro-level air quality problems. Downwinders at Risk’s role in SE Fort Worth is yoking the high tech sensor network with traditional community organizing. In effect, we’re creating a new citizens tool for cleaner air and a brand new guide on to how to use it to get results.

In Plano, city officials want to use the sensor network to help traffic flow and minimize vehicular air pollution. Smart technology is already being installed in the city’s infrastructure, so it’s not a huge leap to imagine installing their 40 sensors on a major roadway for 40 blocks in a row to see how traffic light timing and other variables can be adjusted to minimize internal combustion transportation pollution.

In Plano, city officials want to use the sensor network to help traffic flow and minimize vehicular air pollution. Smart technology is already being installed in the city’s infrastructure, so it’s not a huge leap to imagine installing their 40 sensors on a major roadway for 40 blocks in a row to see how traffic light timing and other variables can be adjusted to minimize internal combustion transportation pollution.

When you begin to realize that the system can not only report conditions, but learn from them and apply that learning to being able to guide not only your own personal health, but the public health policy for millions, you realize how transformational this technology can become. It has the potential to be the most important tool in fighting for cleaner air that we’ve ever seen – because it works from the bottom up and puts the power to change things in the hands of individuals instead of agencies.

We don’t always have to fight the bad guys head on – we can go around them. We can replace them. That’s what makes this network so sublimely subversive. It just leap frogs over an obsolete, regressive status quo.

We should know by the end of next month whether the participants in last week’s call were persuasive enough to convince the NSF to fund the DFW project. Regardless of that decision, the same consortium of colleges, cities and citizens groups is committed to building-out their own 21st-Century air quality monitoring network.